EDITOR’S NOTE: Morry Taylor, the chairman of Titan International, spoke at Lessiter Media’s two national conferences in January 2025 in Louisville. Known as “the Grizz” for his ‘bear-like’ presence – replete with candor and a “call it like he sees it” approach — Taylor has a storied career that began in tool and die manufacturing before becoming a manufacturer’s rep in the heavy-duty wheel business. Following his rise and the eventual acquisition of Titan Wheel International from Firestone, he gained national attention as a GOP presidential candidate in 1996, an experience he chronicled in his bold book Kill All the Lawyers — And Other Ways to Fix the Government. In its last completed fiscal year in 2023, Titan International had done $1.8 billion in sales.

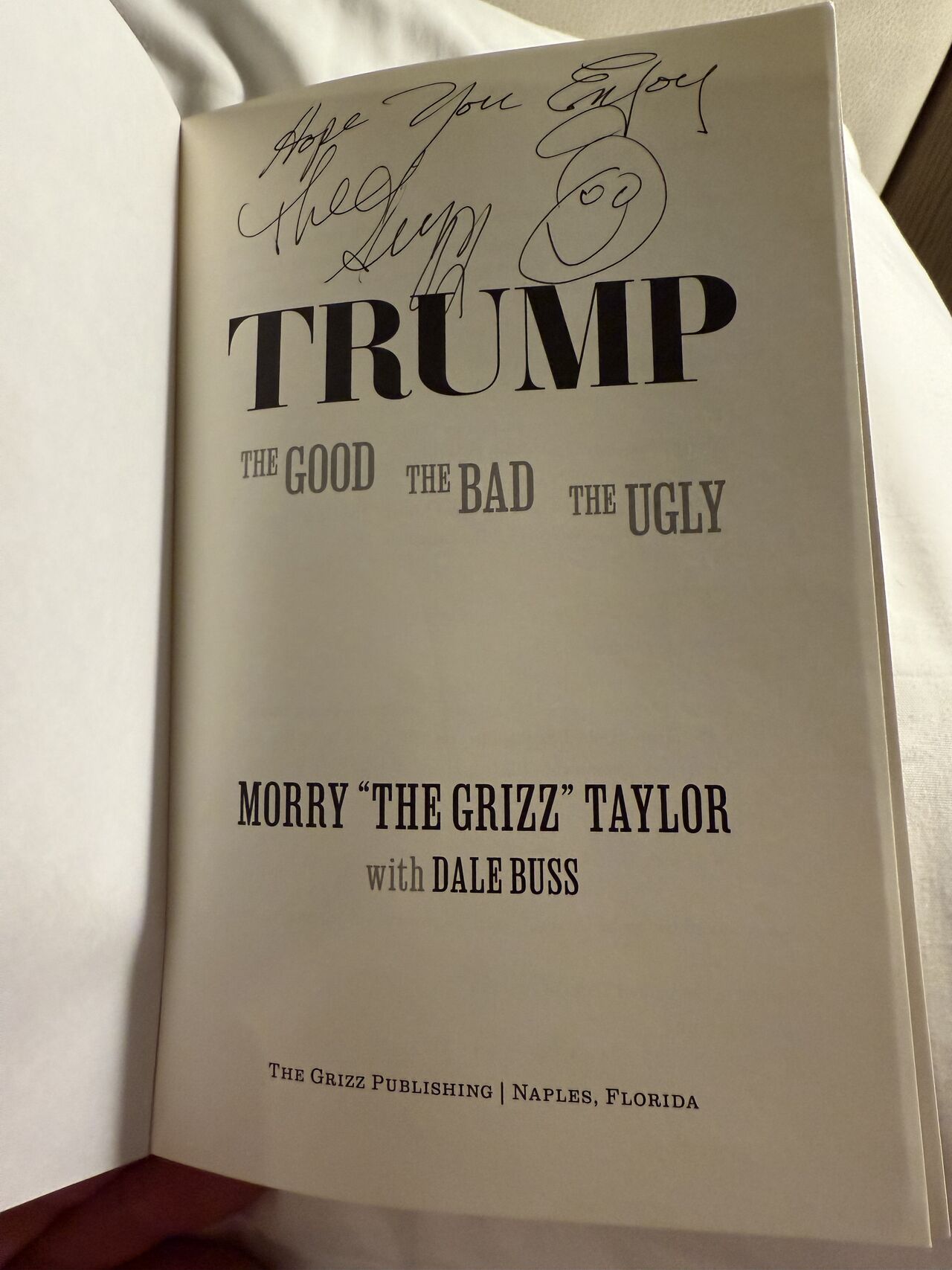

Following his presentation, I got my signed copy of Trump: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, which he and co-author Dale Buss published in 2024 prior to the 2024 presidential elections. Since past histories were so popular with our readership, we sought, and received, Taylor’s permission to excerpt from the book. What follows here is unedited and in Morry’s own words, as it appears in the book, which is available for purchase on Amazon here. – Mike Lessiter, editor/publisher

READ Part I: Where I Come From

READ Part II: If I Had a Bridge, I’d Sell It to You

READ Morry Taylor on the National Debt: ‘The Creeping Menace That Will Destroy America’

By Morry Taylor, excerpted from 2024 book Trump: the Good, the Bad, the Ugly

I put together Titan by using a keen eye for how I could turn around troubled businesses, initially working with my mentor and sponsor, Joseph Tannenbaum, and later growing the company steadily into an industry heavyweight.

In fact, in the seven years after Joe bought it, the business, at first renamed Can-Am, for "Canadian-American," grew to $80 million in annual sales. In 1990, I executed a leveraged buyout with Tannenbaum and Masco Industries, which was headed by my neighbor, Dick Manoogian, and President Bill Billig. Joe got to take some cash out of the company. The deal gave him 40% ownership, me 40%, and Masco 20% in the new company.

In 1991, our business was going well, so the company, Titan Wheel International, borrowed some additional money from our banking group, and I bought Joe's shares back. Let's just say that, on his original $6-million investment, Tannenbaum got back $47 million in just seven years. At that point, my ownership was two-thirds of the company, while Masco's was one-third.

At the beginning of 1992, Titan wanted to buy another company, but our banks wanted us to wait a year. I went to Masco and asked Manoogian and Billig what they thought. Manoogian noted that Masco owned a wheel company in California that did around $20 million in business a year, and that his company would sell it to Titan for book value-about $5 million. Masco would take a note so we didn't have to go to the banks for the money, and the deal would put Titan's sales at over $100 million, which would be good for going public.

Just over 90 days later, Titan Wheel International went public on Nasdaq. One year later, we moved to the New York Stock Exchange, where the company's shares reside to this day. I sold some of my shares for a total of about $40 million.

But back to those first days with our takeover of the Electric Wheel plant in Quincy. At that point, I already was prepared to take the "new" Titan to the next level. For one thing, I knew my way around a factory by then. As a former toolmaker, welder, and industrial engineer, if there was one thing I understood, it was metal. I learned from Joe and from Tony Soave, another neighbor in Detroit who was an enterprising entrepreneur who knew how to build companies, how to look at the value of assets in a different light, starting with the Electric Wheel plant in Quincy.

When I first toured it, the silence that had taken over that huge industrial operation was eerie – all you could hear were pigeons and the constant low hum of the electric transformers that were still on. Looking that over, once I came to the conclusion that, worst-case scenario, there would be a heap of stuff I could sell for at least $6 million, the rest was gravy. Then I had to figure out how many people I needed to hire to start producing wheels again.

With an eye toward the value of used but idle equipment that no one else ever quite seemed to see the way I did, I bought up other closed factories, too. Yet the market for heavy-duty wheels kept shrinking in those days as small-holder farmers gave way to corporate types who bought up their farms, were much more efficient, and reduced demand for tractor wheels. I was consolidating this business.

A select number of Precision Farming Dealer Summit attendees received Morry Taylor's book, Trump: the Good, the Bad, the Ugly in exchange for questions posted to the businessman/author in Louisville.

Another crucial thing I understood was that, in the heavy-duty wheel business, unlike the automotive industry, things changed very little from year to year. Manufacturers just kept making the same designs, so tractor and truck wheels required little in terms of product evolution. I didn't need to worry about buying idle dies that simply would be outdated the next year. As factories failed, I made low-ball offers, took them over, and made them part of Titan.

Around the time of our initial public offering, Titan also acquired our first tire plant, a facility in Tennessee that made wheels and tires for ATVs and lawn and garden equipment. This gave me my first real, integrated look at tractor wheels and tires together, and I realized that the technology behind both kinds of devices had advanced little over the course of 30 to 40 years. So I put together a team of engineers, including myself, to start working on a new approach to tires we called low sidewall (LSW).

The idea behind LSW tires was both simple and revolutionary: They help reduce what's called power hop and road lope, as well as soil compaction, according to research we conducted over the years. Titan has proven that the company's low-sidewall wheel and tire assemblies can save farmers up to 6 percent in efficiency and up to 5 percent in yield gains.

So significant were these gains that, by the end of the 1990s, we were able to persuade Caterpillar to become the first original-equipment manufacturer to offer factory-installed equipment with LSW tires, specifically its line of skid steers. Then we struck an agreement with Goodyear to get a national tire brand behind LSWs. Our sales really took off then.

Interestingly, many years later, car makers would adopt what is essentially LSW technology to create what they call low-profile tires they put on luxury vehicles because of how slick they look. There are some performance benefits for passenger vehicles from low-profile tires, too, though not nearly to the degree they make tractors more efficient. And a lot of people hate them because if you can't drive correctly and you scrape a curb, it doesn't just scuff up a tire-it scratches up your pricey wheel.

Besides overhauling old factories and redesigning the wheel, a major part of what I was able to accomplish in running an industrial company boiled down to human relations.

I made it pretty clear from the start of Titan that I don't suffer B.S. in negotiations. Take what happened after we bought a Pirelli Armstrong tire plant in Des Moines in 1994. The 680 members of the United Rubber Workers there had struck the plant, but I was in no mood to coddle them. Instead, I pulled a Shawn Fain, two decades before the United Auto Workers president theatrically threw Stellantis contract proposals in a garbage can in the summer of 2023 in the lead-up to the union's costly six-week strike against the Detroit Three automakers.

"I made it pretty clear from the start of Titan that I don't suffer B.S. in negotiations ... The union had two thick documents, each of them a three- or three-and-a-half-inch binder, one on economics and one on health benefits. They shoved them over to me. I picked them up and dumped them in a trash can..."

You see, the URW local had a bargaining committee of something like 19 people, and on our side, it was just our labor lawyer and me sitting there. The union had two thick documents, each of them a three- or three-and-a-half-inch binder, one on economics and one on health benefits. They shoved them over to me. I picked them up and dumped them in a trash can. The union boss said to me, "It took us 35 years to get all of that!" I responded, "Another way to say that is that it took you 35 years, you're broke, and that's why Pirelli sold you!"

We settled the strike more or less on my terms. I offered profit-sharing in a contract proposal to the union.

Our U.S. tire plants are unionized, but our wheel plants aren't. You know why? We treat people right. For instance, profit-sharing gave people more skin in the game and the ability to turn hard work and productivity into more income for them and their families. I think the union made a mistake in not going for the profit-sharing I offered.

I still believe that, ultimately, unions get in the way of the relationship between even good employers and employees. However, we made sure our people felt a certain loyalty to those who sign their paychecks, not to the union bosses who take dues out of their paychecks.

For example, we insisted on having regular all-workforce meetings, and the union brass hated them and tried to discourage people from coming. But we made them mandatory: If you missed a certain number of them, we'd fire you. These meetings were invaluable for our relationships with the rank-and-file. People could ask questions of management, and they could all get to see one another.

When I was around, I was always there, in the back of the room. People knew it, and they'd often want me to answer questions. "Are we going to make any money this year?" That was a common one, because each factory had its own financial benchmarks, and if the operation itself passed them, profit-sharing kicked in. I was always honest about where they stood on that, even if it was a tough year.

I played it straight with employees. Like Trump, I've always specialized in telling it like it is — and demonstrating the thick skin to match. At one point at Titan, I walked around plants in a t-shirt produced by the union that had a picture of me and said, "Have you seen the village idiot?" I swapped them a "Grizz" shirt for that. I've been called everything under the rainbow. You've got to learn to live with it.

It really helped that I knew how to do any job in a stamping plant or tire plant. That way, you know what's going on in your factories. I would walk the line and have hourly people explain the job to me if I didn't get it right away. Some people aren't real smart, but they'll beat your ass doing their job day in and day out once they learn it.

I would stop at a guy running a press, take my jacket off, and hand him my phone and say, "Here, you're me for a while" Id have my white shirt on; I'd tuck my tie in; and if for some reason, grease came off the machine and hit me in the chest, I didn't stop. I just kept going.

Otherwise, they'd look at you and laugh about it.

"Our wheel plants aren't unionized. We treat people right. Profit-sharing gave people more skin in the game and the ability to turn hard work and productivity into more income for them and their families..."

I do have a lot of sympathy for the impulse among American workers that leads them to vote in a union. For one thing, they don't make front-line supervisors like they used to. Until the last few decades, the men and women leading production workers on the factory floor typically had risen from among them, having proven excellent at what they did and deserving promotion so they could help others achieve higher levels of productivity in the interests of all.

But starting in the 1960s, the automakers and other giant conglomerates like General Electric decided they had to "professionalize factory-floor supervision, so they required college degrees even for the people on the front line. Then they got even more ridiculous and decided that to become a general foreman in a factory required a master's degree. How idiotic. The recent generations of factory management started out with no idea of what it's like to work in one. But that's what happened, and it has continued.

Along with my factory workers, I had some important management principles for the white-collar people, too. One of my principles came from how I handled it when people got in over their heads. If someone was doing a great job of running a $15-million group and we promoted him to head a $50-million operation, but then it became obvious that he wasn't going to cut it, I had my own way of dealing with it.

If a guy screwed up badly in a leap like that, many CEOs would have fired him. But that's not the approach I took. Implicitly acknowledging part of the problem was that we in top management had misjudged him, I always called him in and said, "This isn't working out. So we're going to put you back where you were without cutting your pay. But you won't get a bonus."

Titan International Chairman Morry Taylor with Lessiter Media's Mike Lessiter prior to the first of Taylor's two presentations to dealers and farmers in Louisville in January 2025.

I did that about 20 times when I was running Titan, and 18 of those people stayed with the company and did better. And after about six months, almost every one of them came up to me and said something like, "I really appreciate what you did. I was in way over my head." Even the wives of 15 of them came and thanked me because these guys were taking the stress home with them when they weren't making it.

Among the best choices I made as head of Titan was picking Paul Reitz, the current CEO, as my successor, who started out as CFO. Paul treats people with respect, gives them support, and does what you're supposed to do when you're in charge. I still serve as chairman and put up with all the crap that the ESG (environmental, social, governance) crowd is throwing at directors of public companies these days, but Paul is running the show.

Under Paul, Titan has continued to prosper, and Titan followed up our record sales and earnings of 2022 with another strong year in 2023 and a promising start to 2024.

"I walked around plants in a t-shirt produced by the union that had a picture of me and said, "Have you seen the village idiot?" I swapped them a "Grizz" shirt for that..."

But the real hero of my accomplishments is my wife, Michelle. We talked every day through all those years of building the company, and she would support whatever I was doing, while at the same time handling everything on the home front. "Blondie," as I called Michelle, would never tell me about the problems she was dealing with in the house, with the kids, the neighbors, whatever, because, as she put it, "He can't do a damn thing about it, so I'll just wait until he gets home." Her attitude was to press on and keep going.

We hardly have ever had conflict. She stays positive, and I try to keep her happy. The Lord has blessed us and our family.