EDITOR’S NOTE: Morry Taylor, the chairman of Titan International, spoke at Lessiter Media’s two national conferences in January 2025 in Louisville. Known as “the Grizz” for his ‘bear-like’ presence – replete with candor and a “call it like he sees it” approach — Taylor has a storied career that began in tool and die manufacturing before becoming a manufacturer’s rep in the heavy-duty wheel business. Following his rise and the eventual acquisition of Titan Wheel International from Firestone, he gained national attention as a GOP presidential candidate in 1996, an experience he chronicled in his bold book Kill All the Lawyers — And Other Ways to Fix the Government. In its last completed fiscal year in 2023, Titan International had done $1.8 billion in sales.

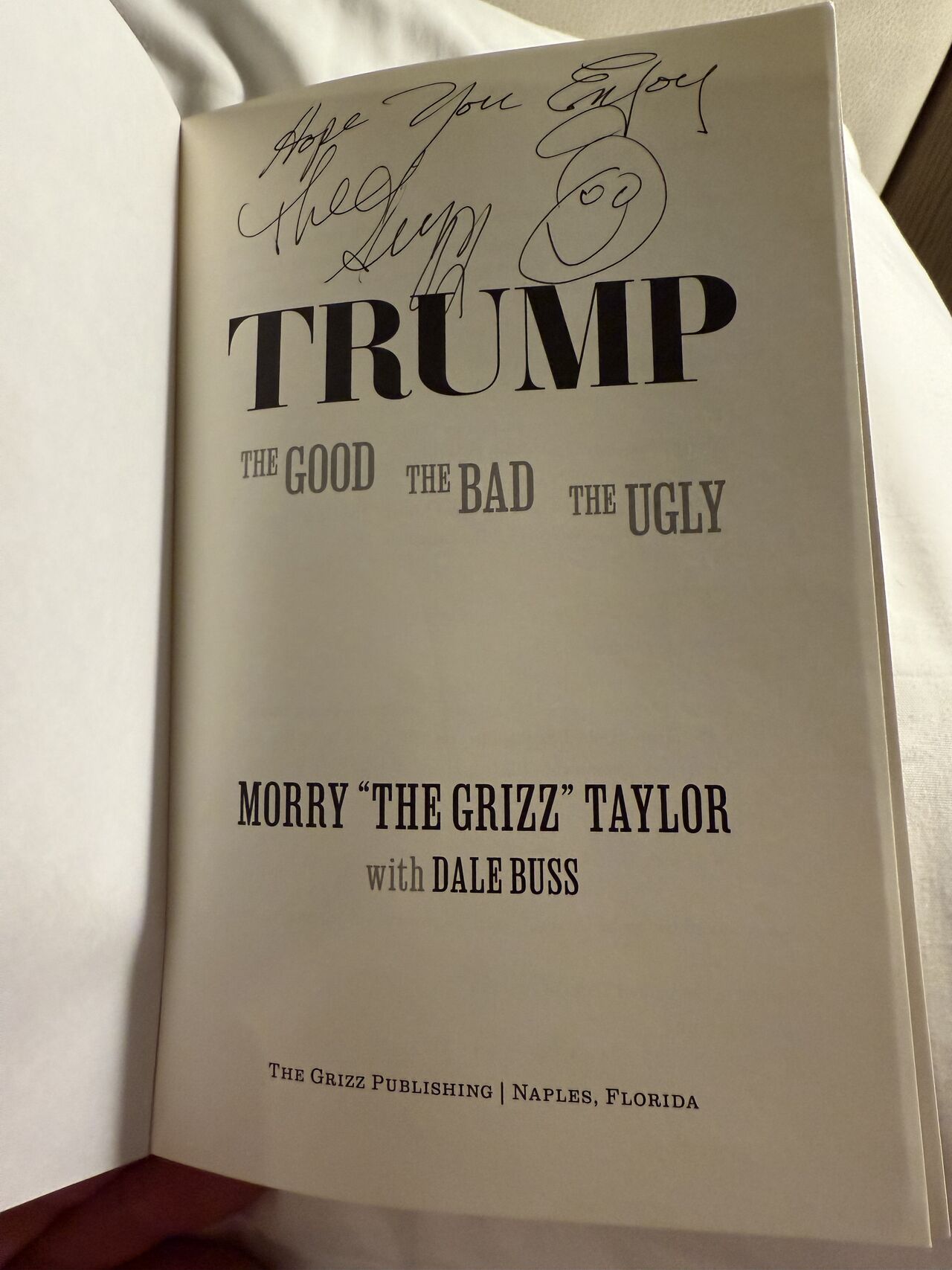

Following his presentation, I got my signed copy of Trump: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, which he and co-author Dale Buss published in 2024 prior to the 2024 presidential elections. Since past histories were so popular with our readership, we sought, and received, Taylor’s permission to excerpt from the book. What follows here is unedited and in Morry’s own words, as it appears in the book, which is available for purchase on Amazon here. – Mike Lessiter, editor/publisher

READ Part I: Where I Come From

READ Part III: What I Learned from Building an Empire

READ Morry Taylor on the National Debt: ‘The Creeping Menace That Will Destroy America’

By Morry Taylor, excerpted from 2024 book Trump: the Good, the Bad, the Ugly

At 28 years old, I could boast of a wonderful young daughter but had a marriage that wasn't working out. I had married an Italian girl whose father worked in Detroit as a mechanic and whose mother was from England; they were excellent people. But my wife needed a lot of attention, and she didn't understand my business or raising a three-year-old girl, and we got divorced.

The divorce included an agreement that I would pay her child support for 18 years, and she would have unlimited visitation rights to see our daughter. She moved to California and got a job with the government, and I never saw her again, though my former parents-in-law stayed in touch with their granddaughter — their only grandchild throughout their lives.

Then I met a wonderful young woman who was working in a bank (and could count cash as fast as anybody I'd ever seen!). Michelle and I had lunch one day, and it turned out that she'd been divorced for about a year — and also had a child, a five-year-old son, Anthony. Michelle and I started dating in 1973, and we got married on August 16, 1975. The years later, we had another daughter, Catherine. Today, we have three children and nine grandkids.

So in 1975, I had a wonderful woman for a wife, but a family to feed. I had left my father's company a few years earlier but not without remembering this thought: He'd always told me that, in Detroit, if you worked and looked hard enough, you could always find a way to make money, I was a good engineer but better than a so-so sales guy, so here was my strategy: I would try to find used equipment to buy and then hunt down someone who was looking for that kind of equipment.

“I was a good engineer but better than a so-so sales guy, so my strategy was to find used equipment to buy and then hunt down someone who was looking for that kind of equipment…”

I would get in the car, wheel out and stop at machine shops, asking the managers if they were looking for anything to buy or sell. That sounds simple, except everyone was "really busy." So they didn't want to talk with me at about nine out of ten stops. I wouldn't even get by the receptionist in the lobby.

The second week out, I stopped at a small tool shop and, by luck, met the owner — who was in the lobby. He was a German fellow in his mid-fifties, while I was about 25 years his junior. Per my routine, I asked him if he was looking for any equipment, and to my surprise, he smiled and said, "Yes, a Number 5 Lucas mill."

Of course, he was smiling because he figured I would have no idea what that was. But I looked at him and said, "That's a great boring machine. I'm assuming you want one in excellent shape." He looked at me, now a little strangely, and said, "How did you know what I was asking for?"

I told him that I'd served my apprenticeship in tool-and-die as well as been certified for welding, and that I was a mechanical engineer to boot. He said, "Really? I'll hire you!"

At that moment, I could have taken the conventional path, grateful to have landed a jumping-off point after my father's company, and proceeded along what might have been a safer career path. But I didn't hesitate to tell him that I was starting my own business and, thank you kindly, would prefer to find him his boring mill.

I asked him his price, and he said, "$35,000." I asked, "Would you pay me 5 percent of the sales price?" He agreed; we shook hands; and I was on a mission. I went to shop after shop, and in the second week, I came into a nice-sized place. Again, for some reason, the owner was in the lobby, and I told him of my quest for a Number 5 Lucas mill.

He had one! And he was willing to sell it at the right price. For him, that was $37,500, because the mill was "like new." I asked him, if I got a buyer, would he pay me a 10 percent sales fee? He offered 7 percent. I told him that, while this was a special machine, it might be difficult to sell at a top price. So he assented to 10 percent and we shook hands.

I'd made my first sale and figured out how to benefit from both sides of the transaction! Now I was going to need a new bank account, business cards, and paperwork filed with the state. The name of the business would be Maurice M. Taylor Associates LLC.

“I would work on commission, selling wheels and machinery, initially to John Deere…”

I leapt into building my own company with a fervor. This country boy was about to show some moxie! I would work on commission, selling wheels and machinery, initially to John Deere. I liked the trade because I knew mechanical stuff, and I learned that I could sell wheels to a corn farmer. Soon, competitors around the world were losing business to me in droves.

Then I got a cold call, from a Massey-Ferguson combine plant in Brampton, Ontario, one of the biggest agricultural-equipment manufacturing factories on the continent. Massey-Ferguson was buying steel rims and making steel disks to weld onto the rims for wheels for their combines, but had stopped purchasing them from their supplier because, well, the rims weren't round. Their supplier was named Titan ProForm Ltd., and it was located in an old building in downtown Toronto.

I figured I would try to fix this situation and arbitrage some profit out of it, which is one of the most common approaches in my modus operandi. Because at that moment I was only about 60 miles away in Brampton, I drove to Toronto, walked into the Titan ProForm offices and introduced myself.

They let me in to see the purchasing guy, and I immediately witnessed quite a scene that told me a lot about why that plant was making and shipping inferior products. There were four desks in the room, and three of them were occupied by schlumps who clearly were just passing the time. The fourth one had a pile of papers on it, and an occupant of a chair behind it who was the only guy in the room wearing a hat. (He would turn out to be Joe Tannenbaum, who later became a key figure in my career.) He was eating his lunch and reading newspapers.

A select number of Precision Farming Dealer Summit attendees received Morry Taylor's book, Trump: the Good, the Bad, the Ugly in exchange for questions posted to the businessman/author in Louisville.

Given a minute over their apparent lunch break to explain my unannounced and uninvited presence in their office, I told them I was a manufacturers' rep who’d been visiting various farm-equipment manufacturers, and I knew that Titan ProForm didn't have any of the business from these Original Equipment Manufacturers. The general manager, a Mr. Katz, politely told me that Titan dealt with everyone, and that they didn't need some new manufacturers' rep shilling for them.

I took another look around and concluded that either Mr. Katz was lying or stupid. I told him thanks, left a card and walked out. On my way past the secretary who'd shown me in, she asked why I was there. I told her about the conversation I'd had with Massey-Ferguson about Titan's rims, and that while I knew little about the wheel business per se, I knew something was wrong at Titan somewhere. She laughed and said, "Sure, it's right here."

I kept digging into the obvious problems at Titan and finally was able to pounce on the situation. I learned among other things that Titan's main competition was the Electric Wheel Company in Quincy, Illinois. The Electric Wheel plant there had gone on strike, so everybody producing rims for combines had to put their equipment up on blocks until the strike was over.

“Deere, one of the biggest agricultural-equipment makers in the world, was desperate to get some wheels to put on their combine chassis — and get them out of their factory…”

John Deere, one of the biggest agricultural-equipment makers in the world, was desperate to get some wheels to put on their combine chassis so they could sell these expensive machines and get them out of their factory. So I made my way to their top factory guy and asked him if I could get a deal with him if I could promise to deliver him some badly needed wheels. He said yes — he’d order 200 wheels from me, and he didn't care where I got them, Titan or somewhere else, but they’d damned well better be round!

It was the biggest order I had gotten to date as a rep. I threw all my stuff in the car, told Michelle I'd see her in a couple of weeks and drove the four hours from Detroit to the Titan plant near Toronto, getting there at six a.m. on a Monday so that I could personally supervise the formation and assembly of these precious wheels.

And that's exactly what I did. I rolled up my sleeves as never before, showed the Titan plant workers exactly what they needed to do, step by step, right out on the factory floor with them — how to weld them; what to paint on the wheels; and what not to paint. All the while, I fought through language and skill barriers, heat, and the intense stakes involved.

“I showed the Titan plant workers exactly what they needed to do, step by step, right out on the factory floor with them — how to weld them; what to paint on the wheels; and what not to paint…”

Soon after, word of the ruckus I'd caused had gotten upstairs, and Tannenbaum himself appeared. Turns out he was the owner, and Katz, the guy who'd told me I wasn't needed at Titan, was his nephew.

Tannenbaum closely followed my actions that day in helping his company take advantage of the opportunity with Deere that I had created for them and myself.

“I stopped home long enough to take a shower and kiss Michelle, and then I dashed off to Deere to enjoy the fateful moment of overseeing the delivery of 200 wheels we'd put together within a couple of weeks…”

We managed to put together 200 beautifully round wheels within a couple of weeks, and they were shipped to Deere in the Quad Cities. I stopped home long enough to take a shower and kiss Michelle, and then I dashed off to enjoy the fateful moment of overseeing the delivery of the wheels to Deere. The boss there was thrilled, I got more orders from Deere, and Maurice M. Taylor Associates was on its way. After that performance, I was already Tannenbaum's unofficial right-hand man, and I started repping more wheel manufacturers.

After a while, I was able to get maximum leverage out of my performance and my growing reputation. In the early 1980s, I honed in on the fact that the Electric Wheel plant was owned by Firestone, and that it had about 65 percent of the U.S. tractor-wheel business at that time. But tractor sales were declining, and Firestone wanted to find a buyer or close the UAW-represented plant in Quincy, where the union wouldn't consider contract concessions.

I saw an opportunity for both Titan and me to make some money and do a long-term deal to take advantage of how Firestone was abandoning Electric Wheel and the market.

Tannenbaum and I had a great and rather unusual relationship. The Orthodox Jewish community is a very close-knit one, and Tannenbaum was a devoted and prominent member of it. For example, Joe gave millions of dollars to Orthodox causes, and one time many hundreds of people from the Jewish community and beyond feted Tannenbaum at a huge birthday party in the Sheraton Hotel in Toronto.

But I was a goy. He appreciated my candor with him about his business but, more than that, he told me he liked my moxie. Business moxie was something that his three offspring didn't have and couldn't give to Titan, so when Joe found it in me, he treasured it — and me. In fact, Joe would often jokingly insist that one or the other of my parents-or both — were secretly Jewish. Sometimes he would muddy my identity at some risk to himself.

For example, frequently, Joe would host prominent rabbis in his office. One time, the chief rabbi from Israel was in Toronto visiting Joe, along with some associates, and he was meeting with them there. I had to bust in because of some emergency in the plant, and I apologized to the esteemed clerics, but I said, "Joe, here's the situation." I described it to him and made sure he authorized me to go fix it. So Joe sat there, also apologizing, and told these rabbis that my mother was Jewish! The man in charge of Tannenbaum's foundation also apologized for me and reassured them there were no gentiles in that room.

I admit I take some pride in the relationship I had with Joe. A true giant of Canadian industry, he was at one point the biggest landowner in Ontario. I'm a gentile yet I worked essentially as his right-hand man in the United States for several years, happily and effectively. That was a testament to how good a mentor he was, and how good a man, and I guess a testament to how eager I was to learn. Or maybe he just liked the kosher sausage and bread I'd take to him when I went to various project sites.

Titan International Chairman Morry Taylor with Lessiter Media's Mike Lessiter prior to the first of Taylor's two presentations to dealers and farmers in Louisville in January 2025.

I got it. I was the only guy Joe had who really understood what went on in factories. When I walked through the Electric Wheel plant in Quincy, I didn't have some grand vision for what it could become or how to turn it around. It was simple: I would call up Firestone and see how much they wanted for the closed plant. On my drive home to Michigan, I pulled over for gas in Indiana and called Firestone in Akron and asked an executive if he was the person who could make the decision on the plant, because I had the guy who could write the check.

The Firestone guy told me $6 million was the price, not a dollar less. This was December 1982. The next week, I drove to Toronto and told Joe he should go look at this plant because someone else might buy it. I chartered a little plane and we flew to Quincy the following week.

We went on a plant tour. After we left the Quincy plant, Joe told me to offer Firestone $10 million cash. I told Joe I already had a deal to buy it for just $6 million! He smiled and hit me in the arm. "Great!" he said, and Joe and I made a deal on the flight back: When they sold us the fac-tory, I got $4 million, plus he signed me to a 15-year contract to run the factory, and my company would do all the sales of the stuff made there for commission.

Now, Maurice M. Taylor Associates was on its way again!