Editor’s Note: I first heard about a dealer known as “The Turk” shortly after our company acquired Farm Equipment in 2004. I’ll admit that I didn’t know his real name (Orhan Yirmibesh) for years, but Johnson Tractor’s Leo Johnson, who grew up across the street from him in Clinton, Wis., continued to share stories of the legendary Turk. The stories from Johnson, along with a “beyond the grave” letter from industry icon Bill Fogarty, provided more lore on the Turk. Yet due to what I heard was Turkish culture surrounding death and estranged family members, putting the pieces together on his career was more difficult than anticipated.

Following is what several historians and numerous interviews with area farmers, other dealers and most notably his 78-year-old daughter, revealed about the man, nearly a quarter-century after his death.

We went deep into the annals of farm equipment history for this Hall of Fame selection for a man whose heydays were in the 1950s-60s. I suspect that he could’ve written the book on the “sales velocity” concept before the term was coined for business school vernacular.

Here are some observations from the study on this maverick dealer who introduced new concepts to the area and the industry.

-

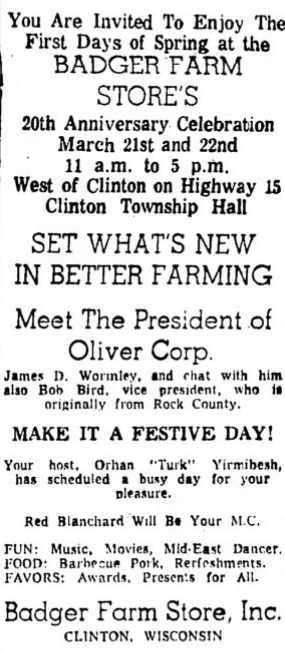

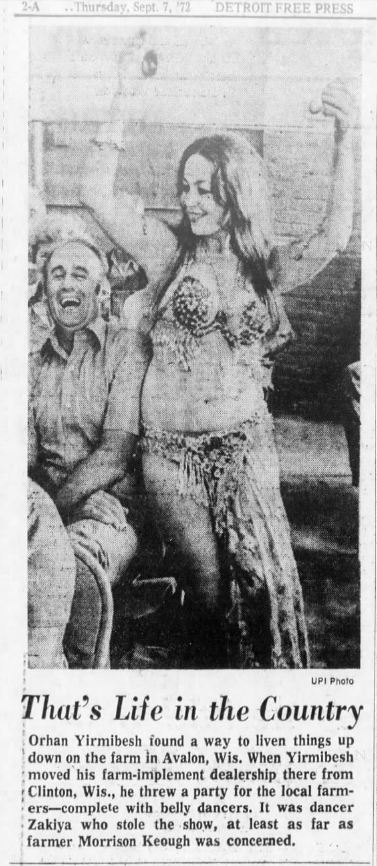

He ran an unbelievably lean operation with no full-time salesmen beyond himself, but freely hired belly dancers to entertain at customer events.

-

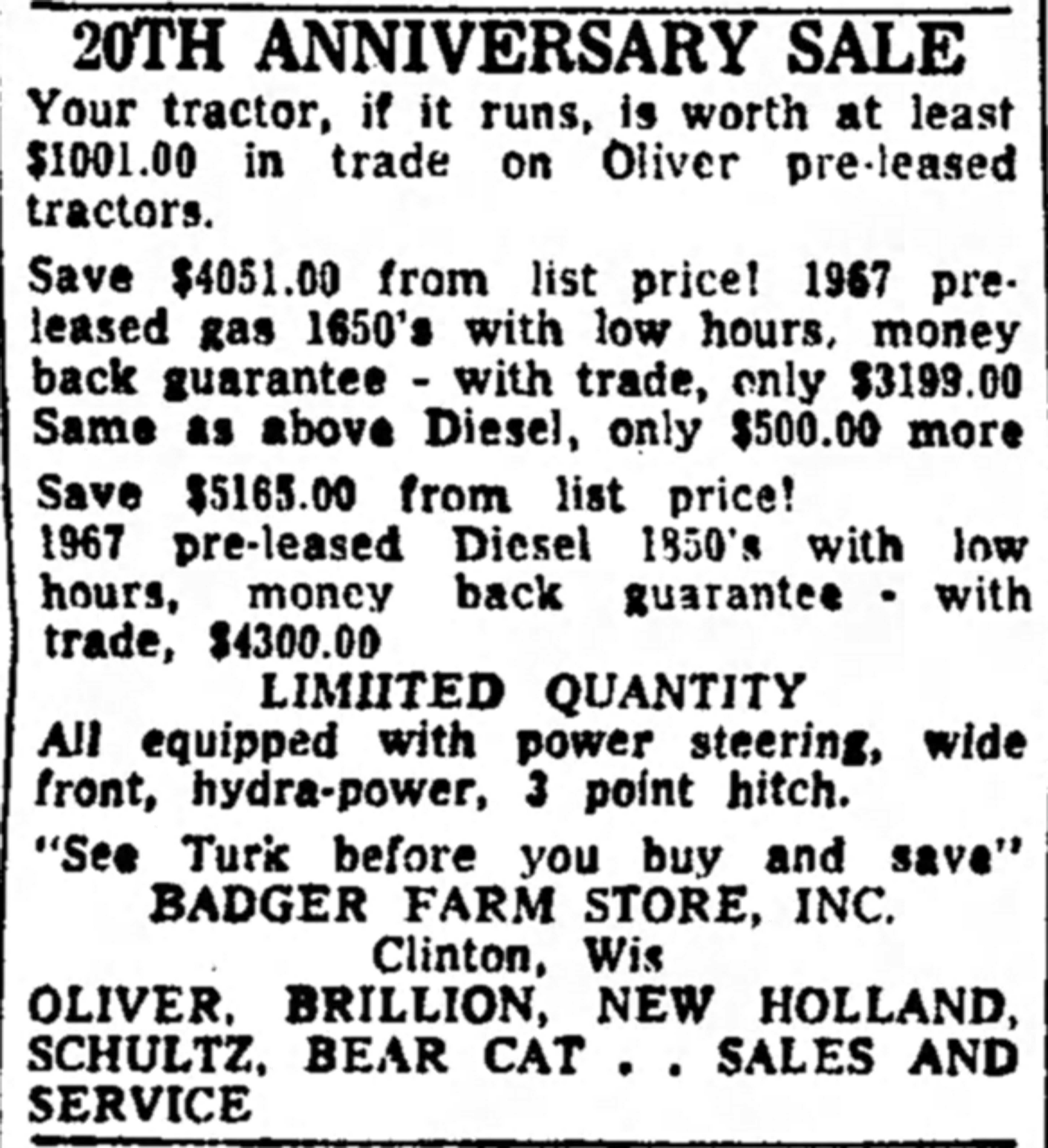

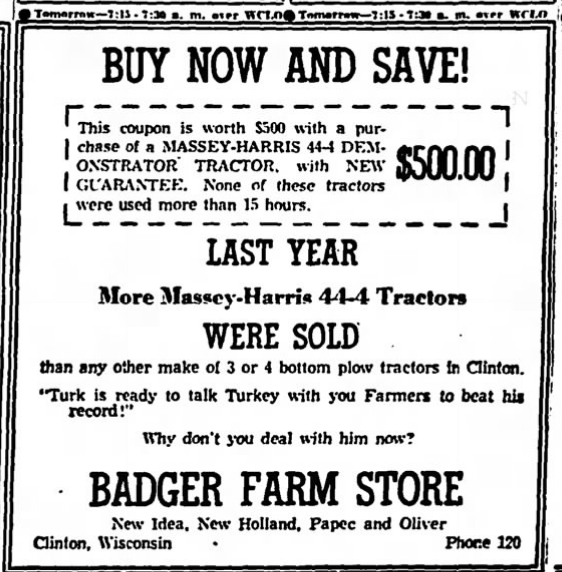

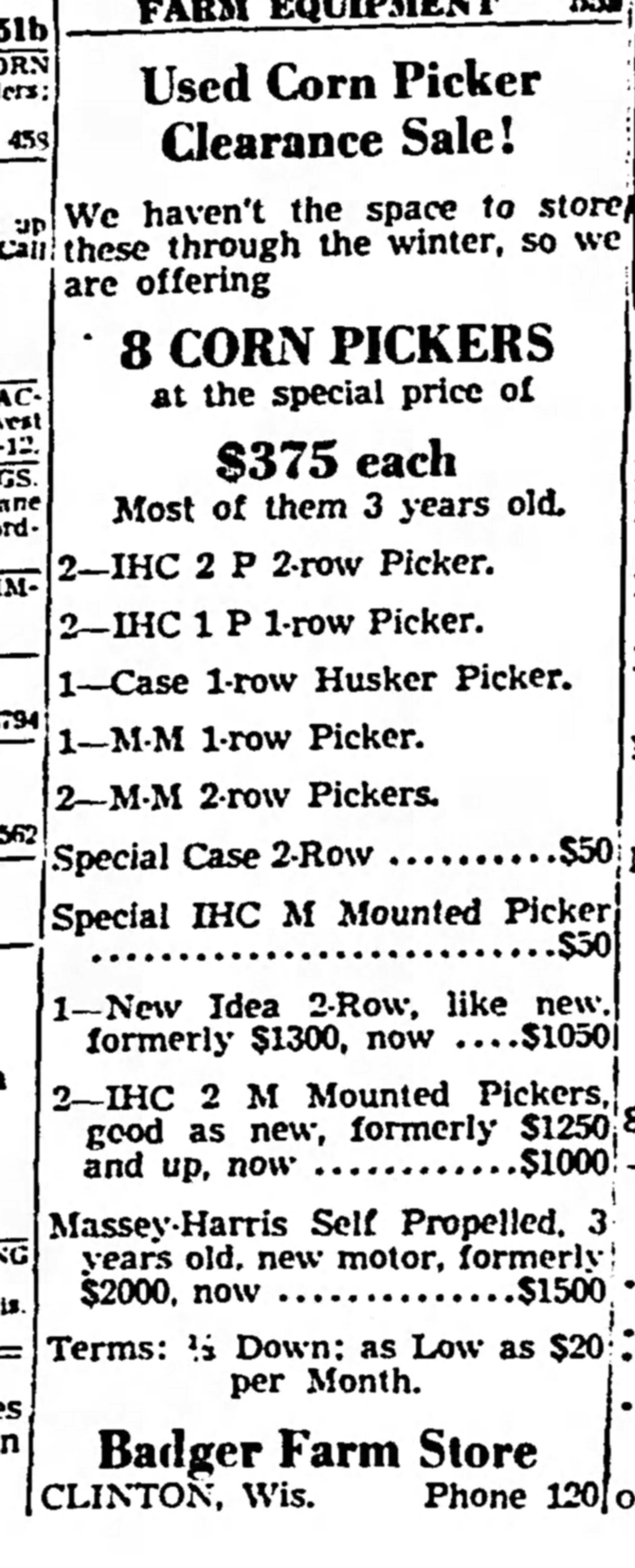

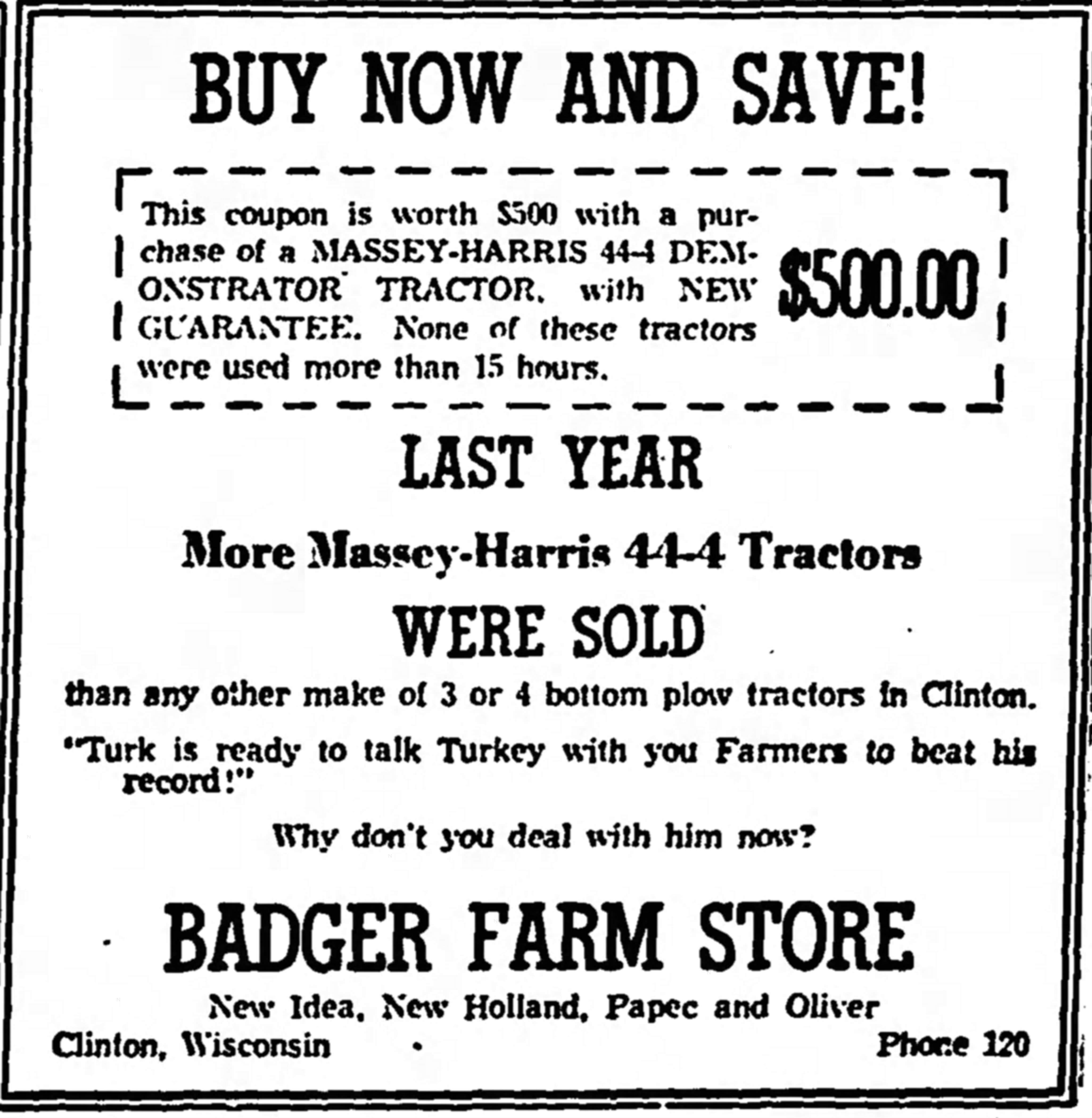

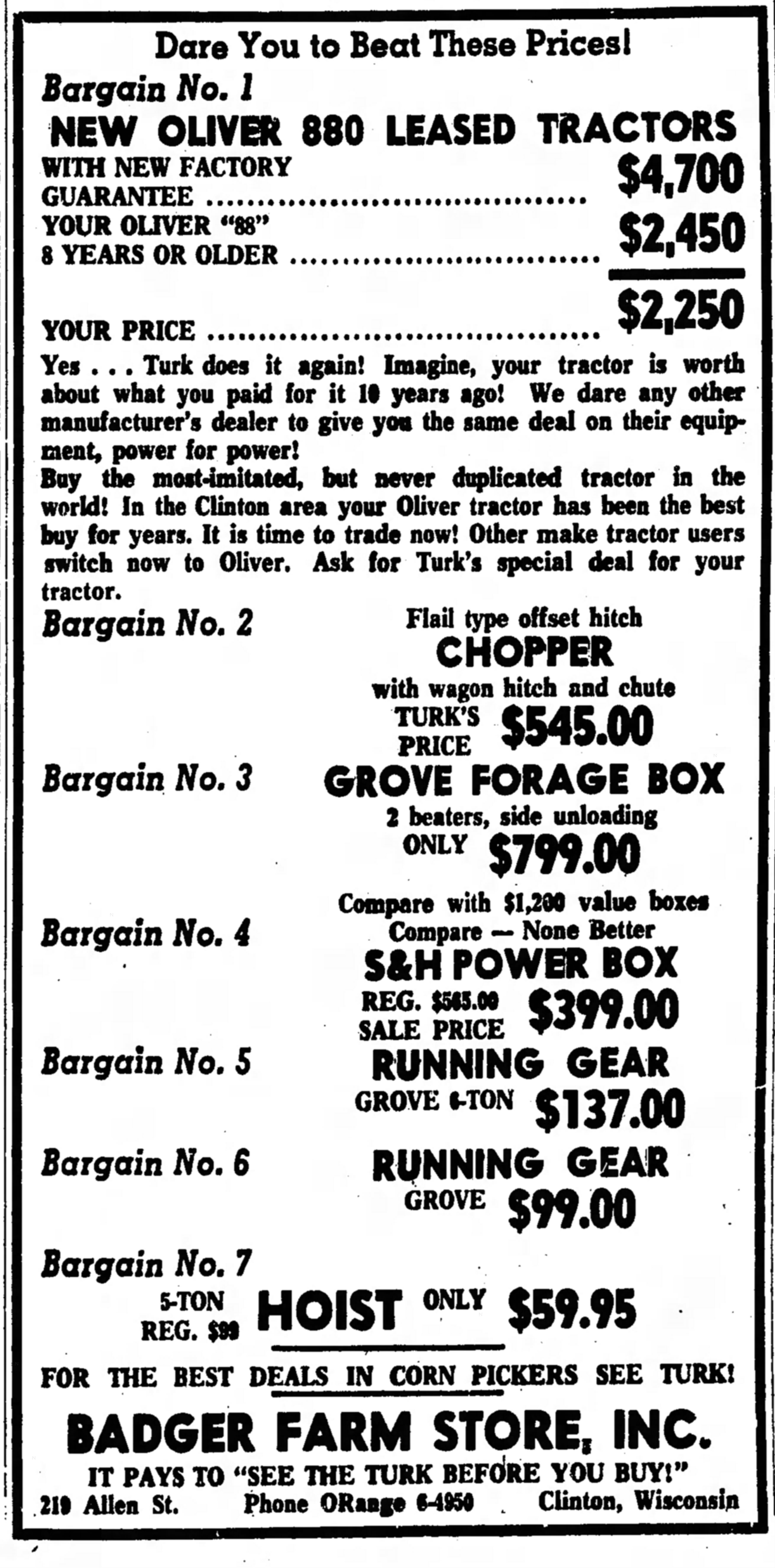

He was “volume at all costs” and a marketer with aggressive and humorous slogans.

-

He was unpopular with dealer peers who couldn’t compete with his low prices and whom got locked out of the profitable cannery business. He managed to do it by buying in bulk, operating with skeleton-crew overhead and opting for jockeys instead of full-time salesmen.

-

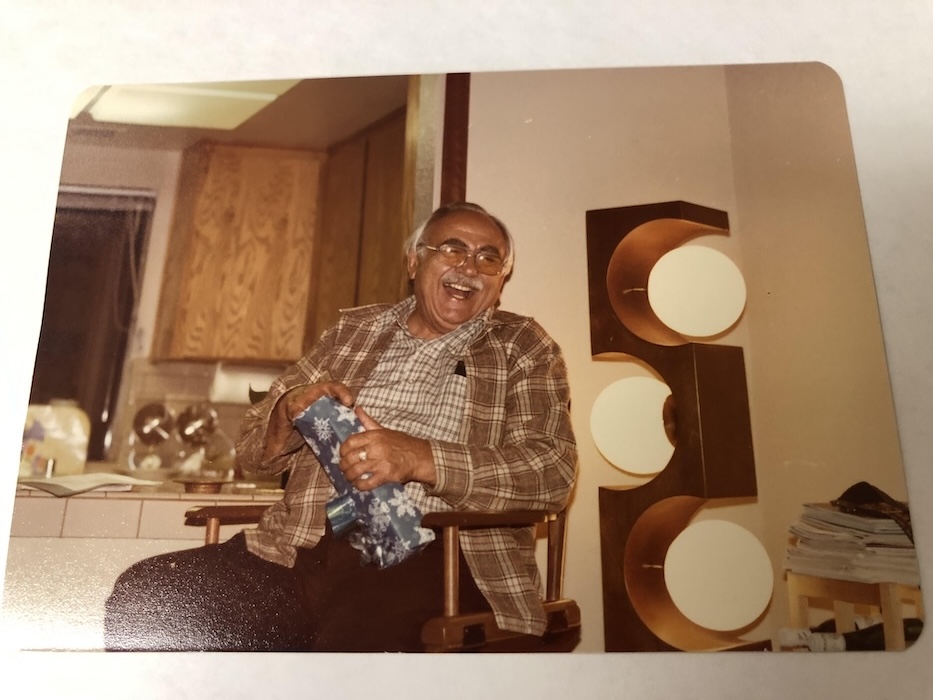

He had a public and private persona, says his daughter, Sevim (Sue) Larsen. While he acclimated to American business culture amazingly well, his controlling nature at home with his wife and only child led to estranged and unfortunate final years.

A Serendipitous Career

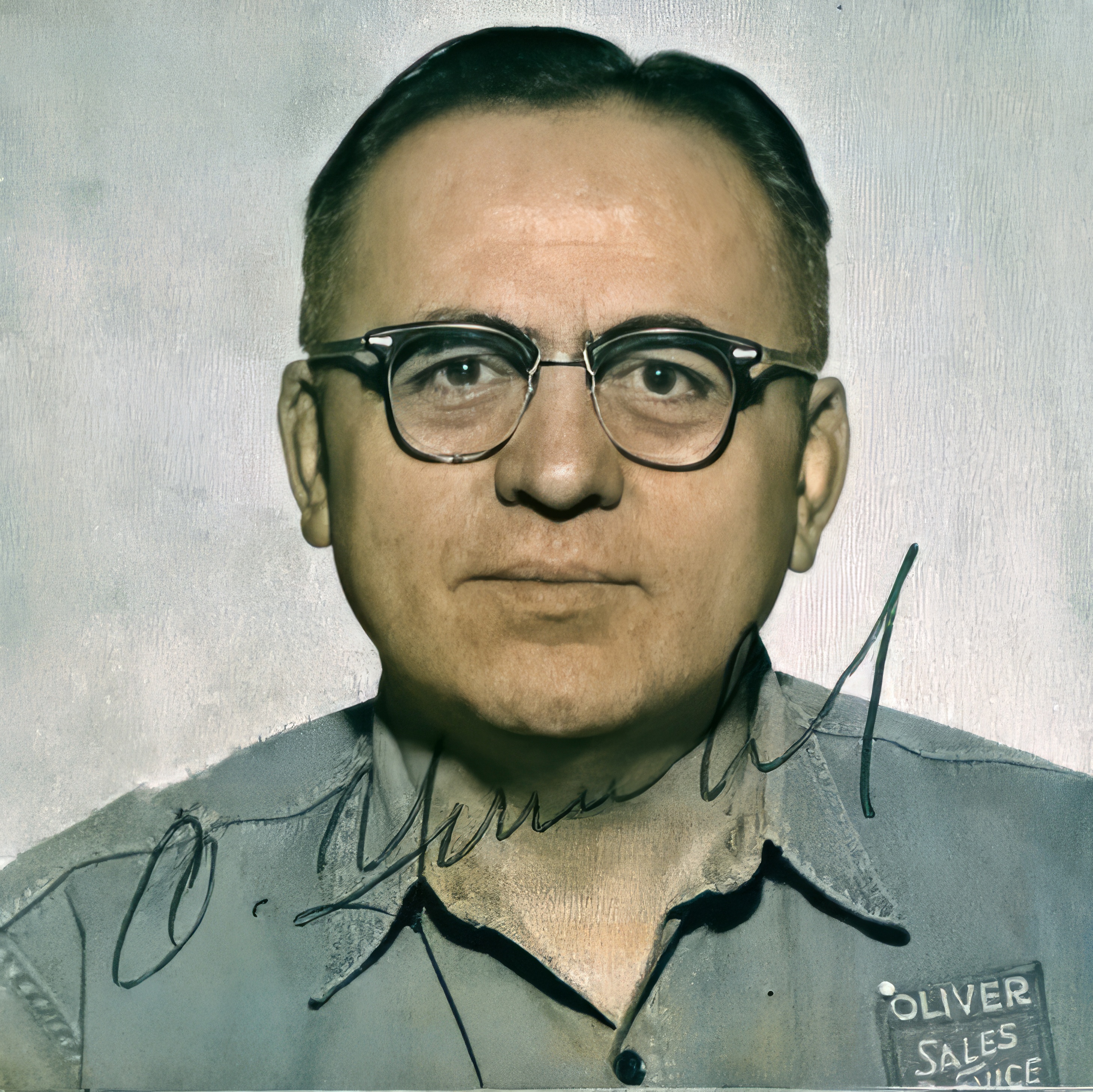

According to Clinton's historian Tom Larsen, Orhan Yirmibesh was an Istanbul native who attended an all-male Turkish boarding school from age 8 on and graduated from American Robert College. In 1936, he arrived at the Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison to pursue a graduate degree in economics.

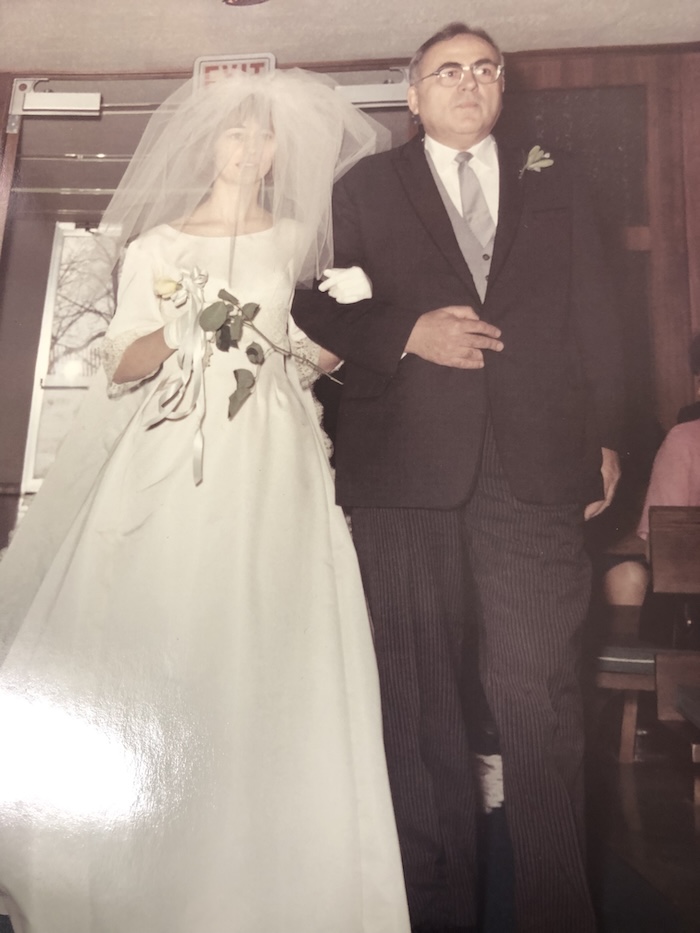

It was there that he found love in Ruth Zeidler, who’d changed his career trajectory. He and Ruth had a daughter, Sevim, in 1945, who is now 78 and lives in Sacramento, Calif. Her husband, Eric Odegard Larsen, passed away in 2013.

Bill Fogarty on the Turk: ‘The Dealer Most Ahead of His Time’

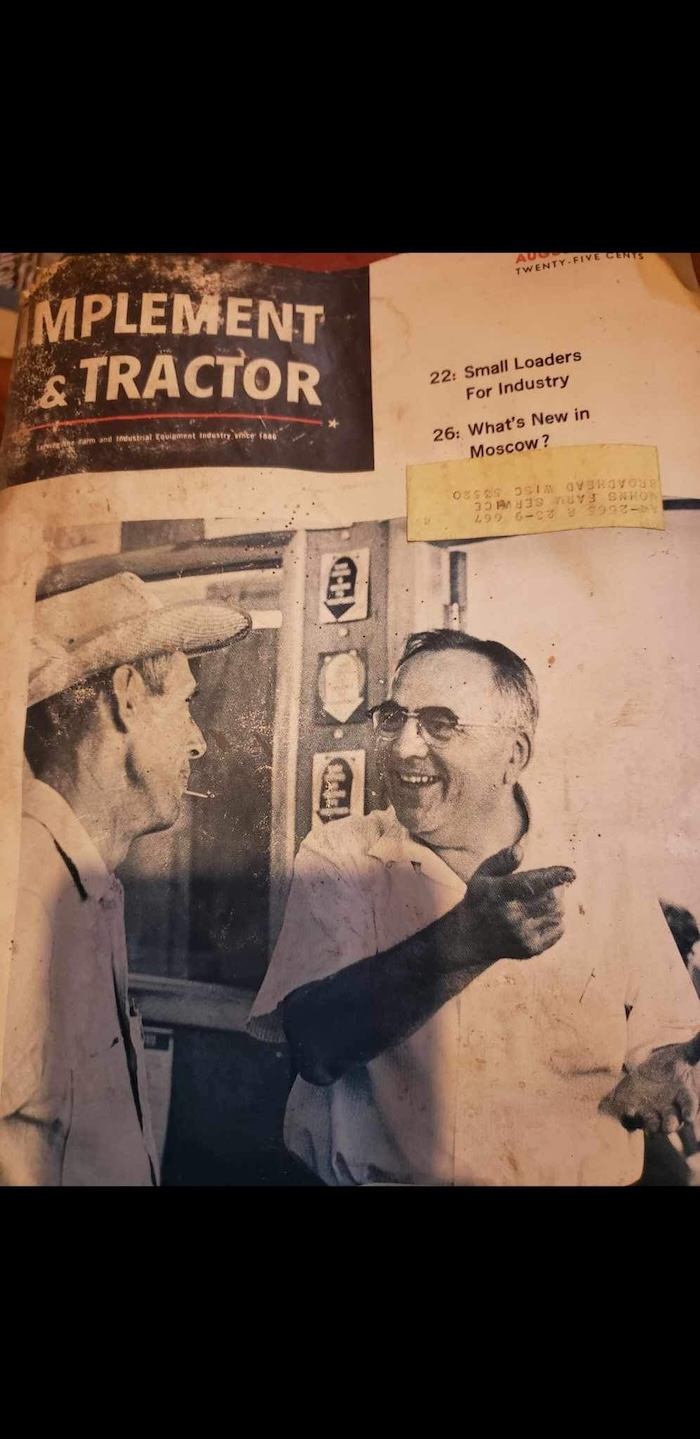

In the November/December 1998 “Best of Bill Fogarty” edition of Farm Equipment, the iconic editor of Implement & Tractor and Farm Equipment described Orhan Yirmibesh as the dealer "most ahead of his time."

“The Turk didn't have the most progressive shop or the most brilliant sales compensation plan or the most dazzling showroom floor. But he understood the values a dealer can offer a customer beyond the iron itself. He got an Oliver franchise after World War II and soon noted the presence of a number of vegetable canneries in the area. He found out they would be interested in leasing tractors on a short-term basis, usually 7 months.

“So he launched a program to accommodate them and then, when the tractors came back, he sold them to farmers in his area at very attractive prices. Everyone was happy, and he had provided something special to all parties.

“And today, about 50 years later, some dealers understand what Turk did back then: You can get by as a provider of machines and services, but it's also possible to provide another very great value — the flexibility that many customers need with regard to the use of their money.

This is what auto dealers learned a long time ago. Not many in the farm equipment business have seen what Turk saw in the 1940s.”

Sevim says her father’s original plan was to return to Turkey and operate an import/export business with an old boarding school chum. But love and luck had other plans.

“His roommate, Freeman Kemmerer, was from Clinton and was working in securities and traveling to the banks in the area. My dad asked him to find a car dealership to run until his export business could come together. Freeman found a farm equipment business for sale in tiny Clinton, a town of about 1,000. He purchased it and became a silent partner with Dad.” But she quickly adds things were never exactly silent “because they fought like mad dogs.”

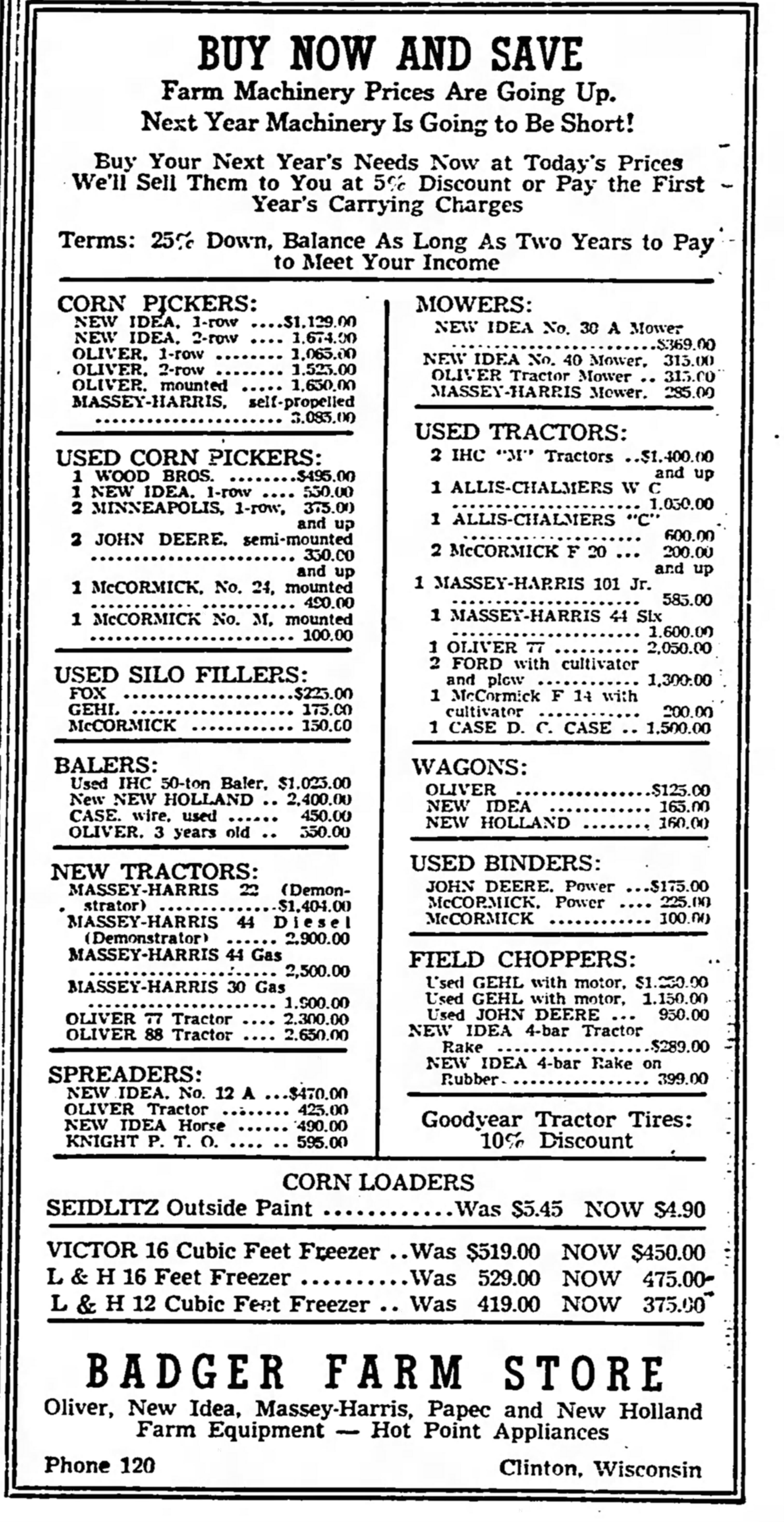

According to the Clinton Historical Society, the Badger Farm Store was founded in August 1948 with the Yirmibeshes, Forest and Kemmerer as incorporators. The capital value was established at $40,000 divided into $1,000 shares, which soon increased to $100,000. The Turk acquired the Oliver tractor contract to anchor the business, which also carried New Idea implements, farm supplies as well as Norge home appliances and DuPont paints.

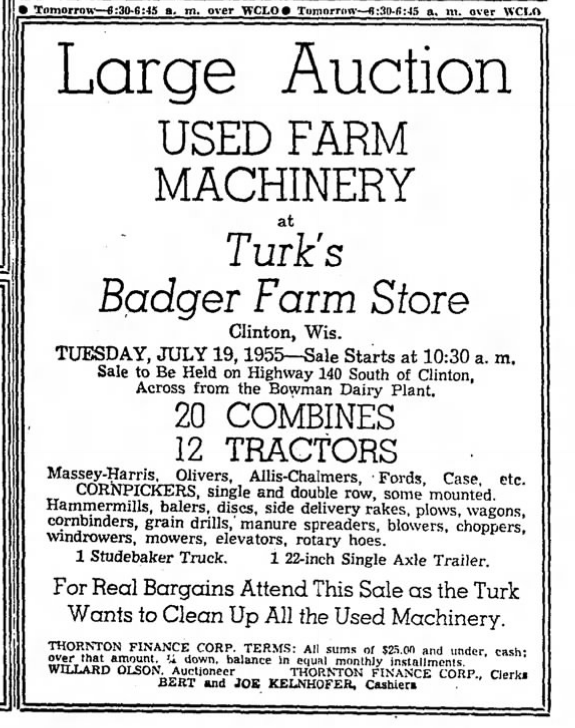

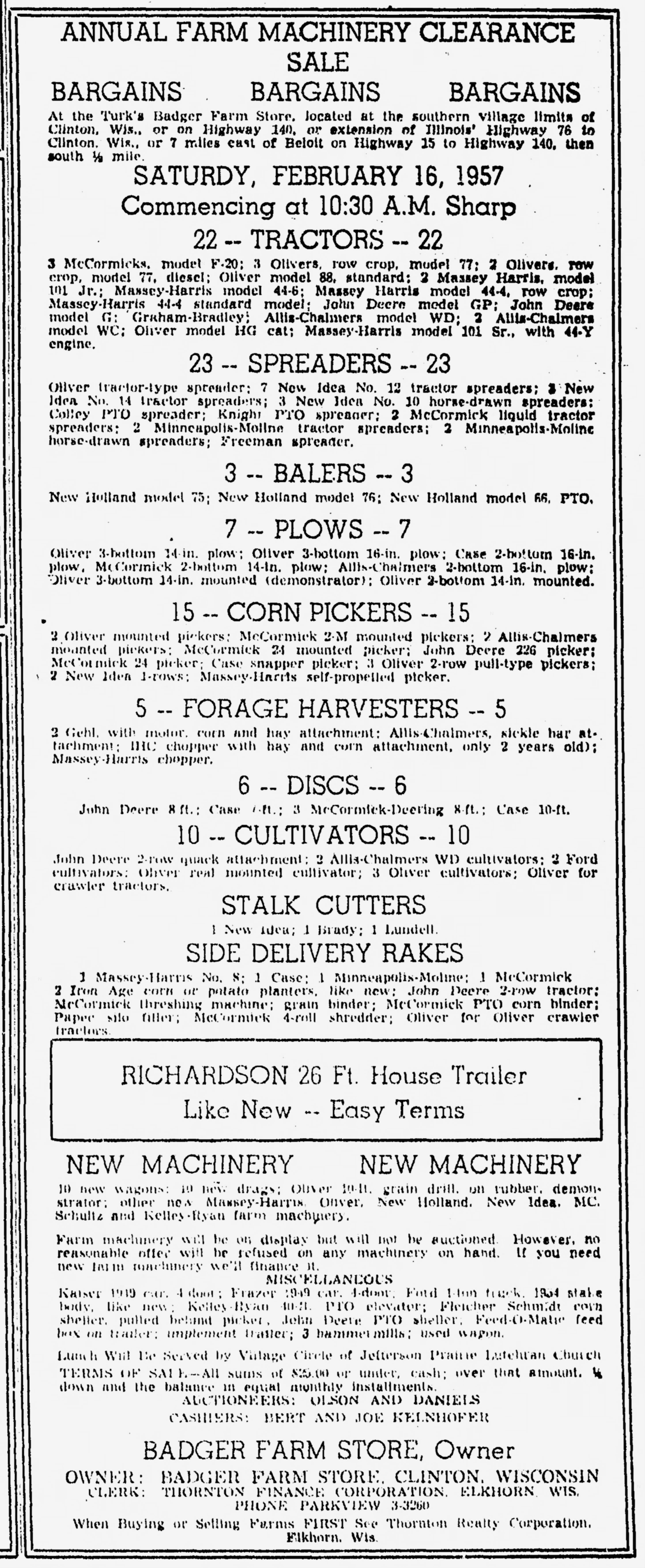

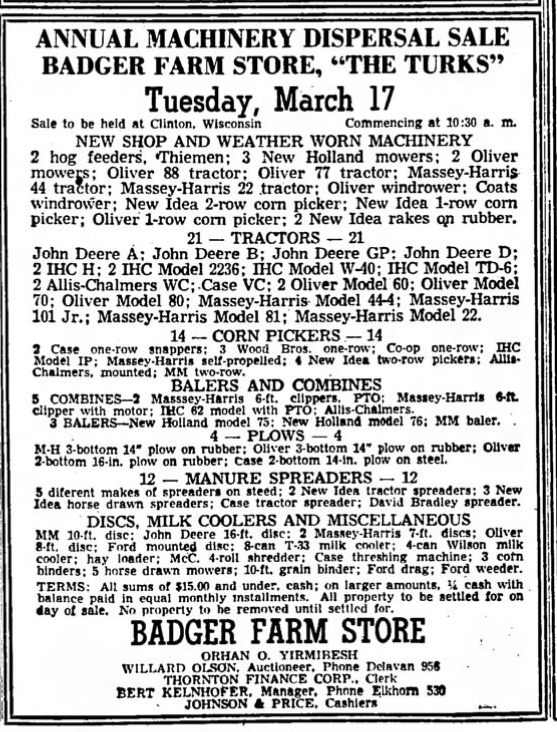

Larsen recalls that the Turk was known for his annual auctions to dispose of the masses of iron he’d taken in on trade. “People came from all over to attend his auctions,” says Sevim as she recalls the ads listing hundreds of tractors with slogans like “See the Turk Before You Buy” or “Come and see the Terrible Turk.” She adds that church volunteers fed everyone and “of course he showed off the trademarked belly-dancers.”

“Even as he wanted to exit, the business was coining profit. He didn’t worry about selling the hundreds of tractors he was ordering. He just put them out there and let somebody else pay for them over and over, and he pocketed the money. He didn’t give a hoot about being an ‘important’ equipment dealer

…” – Paul Wallem, fellow Hall of Fame dealer who competed and learned from the Turk in the late 1960s and early 1970s

The Turk became a U.S. citizen in 1955. He, Ruth and Sevim were active in the community and he served as village president in 1959-60.

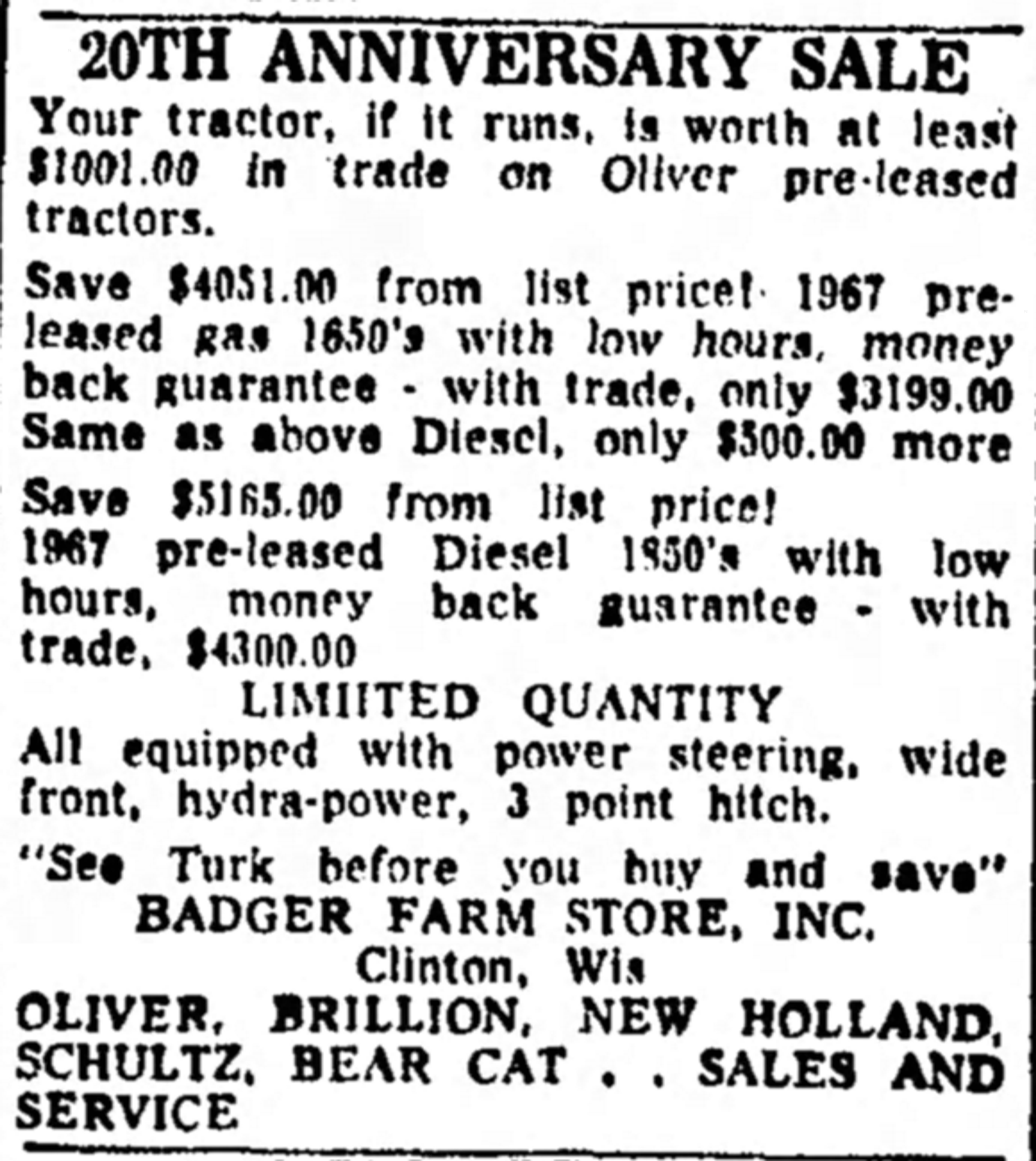

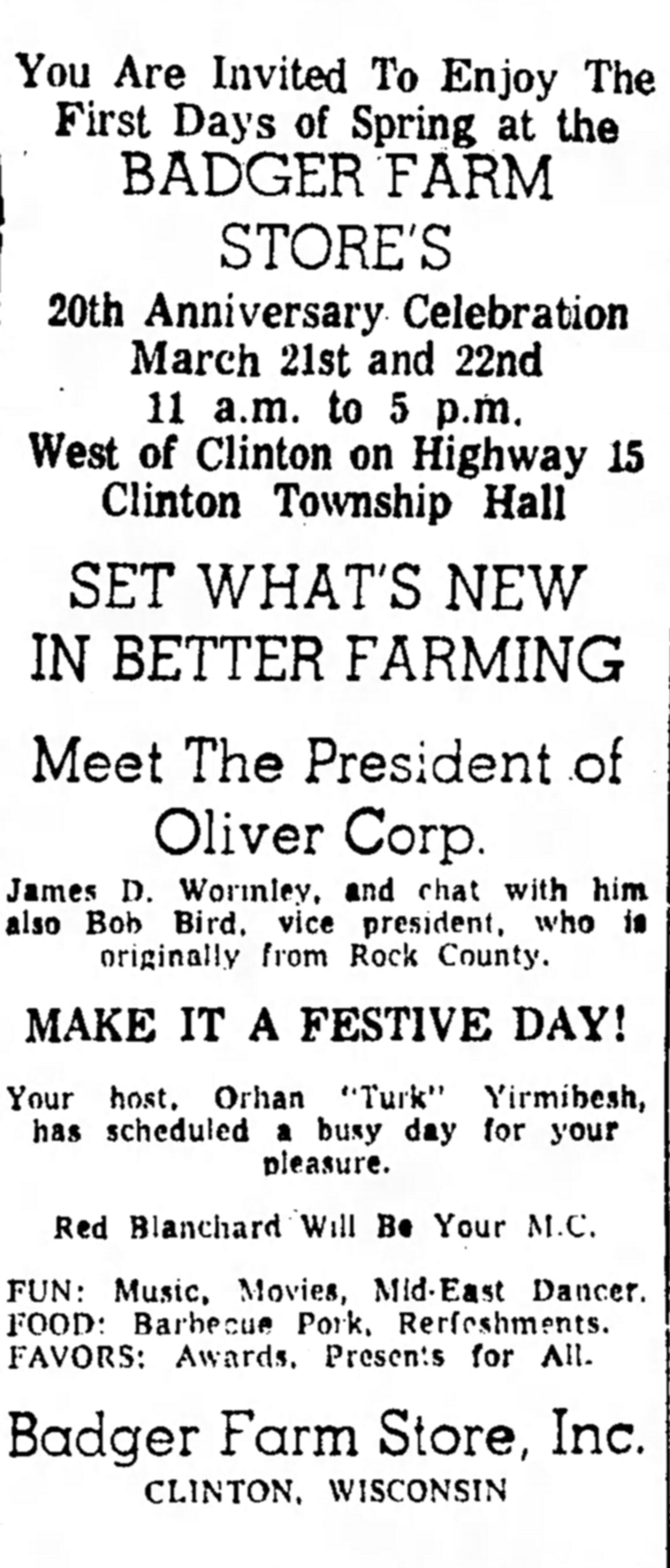

In 1969, he organized a 20th anniversary event for Badger Farm Store at Clinton’s Town Hall. The event was hosted by radio showman, comedian and country musician Red Blanchard. The event featured barbecue, movies, live music and "middle-east dancers.” The president and vice president of Oliver Corp. were also on hand for the occasion. He repeated another blowout party 3 years later to celebrate the grand opening of his new Avalon, Wis., location.

Success came despite some prejudices against him as a Muslim and language barriers. But he was destined to be unique and unforgettable in nearly every way possible. And maybe the belly dancers softened the minds of some stiff-necked farmers.

Canneries & Leasing

The niche that the Turk penetrated with his green Oliver tractors – the canneries of Green Giant and Libby’s – shows how much the industry has changed from pea viners (shellers) and pull-type combines to today’s FMC combines.

The Olivers were reportedly the tractor of choice due to their running gear design for operating at slow speeds so that the pull-type combines wouldn’t plug up with the wet peas. In those days, the Olivers were driven in reverse as the crop was cut and arranged into windrows for the pull-type combines to pick up the peas.

Sevim recalls how little her father knew about the tractors in the beginning. He once was asked about the speed at which the Oliver could pull a plow and he ventured a guess at 45 mph.

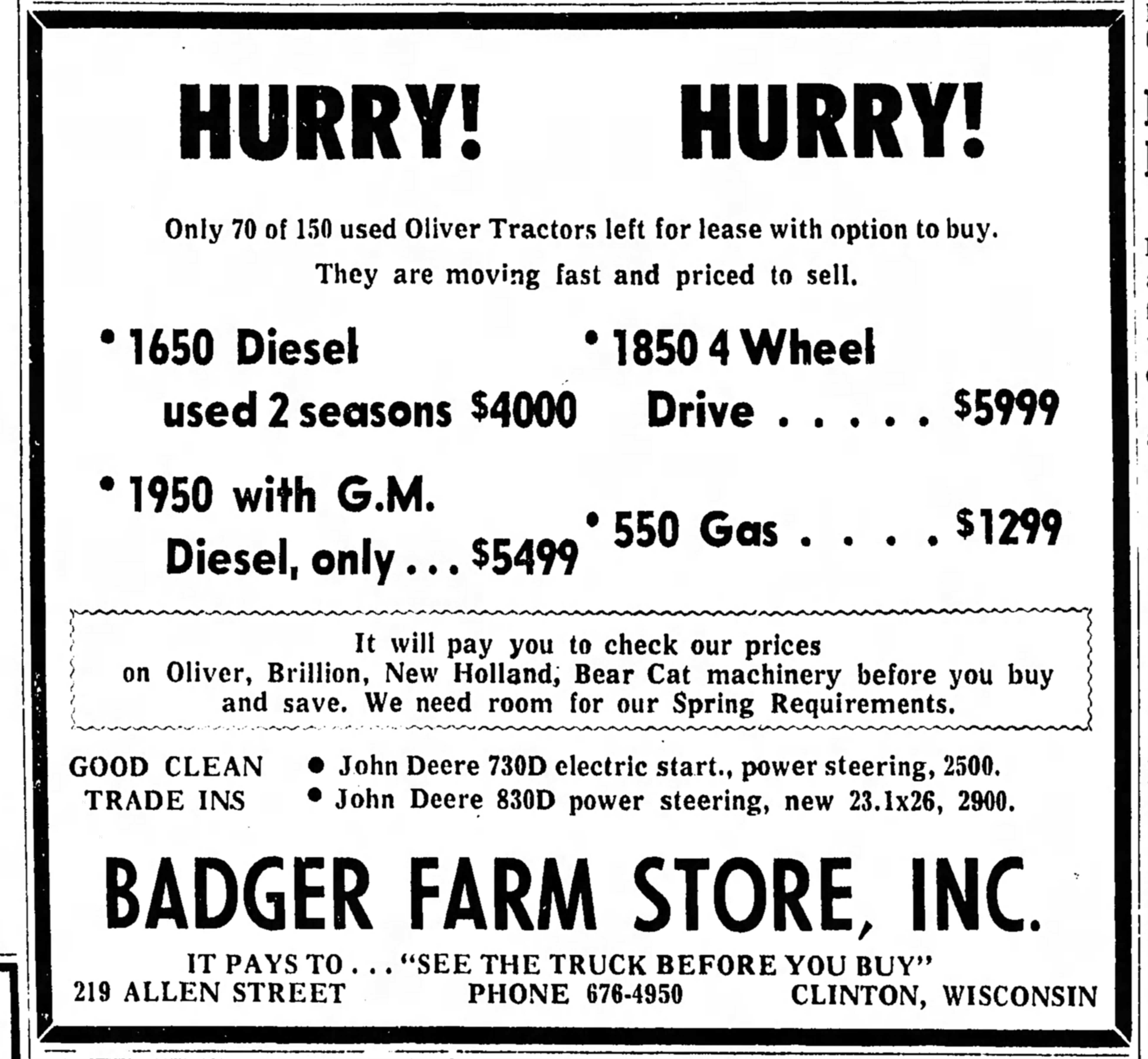

Johnson Tractor's Leo Johnson says the Turk figured out he could buy a larger number of new Oliver tractors at a bulk discount each winter and lease them for a ridiculously low amount to farmers for spring work. After a couple of months with the farmers, he’d lease them to the canneries for pea harvest and wagon-pulling. As soon as they were done, he rented them out for fall tillage. He occasionally would sell whole fleets and would retail a few, but the majority were moved via a couple of reliable jockeys.

Ross Rieckers of Seymour, Ind. (also known as “The Oliver Man”) says the Turk was buying tractors by the rail carload from Oliver, which meant he got a great price to sell things cheaper than any other dealer. And because he paid cash, Oliver didn’t have any control over him or the deals.

Rieckers says he also looked out for his next customer. “If the canneries did a lot of service work to one particular tractor, he’d make sure the customer knew that that tractor had a lot of troubles, or he wouldn’t sell it unless the farmer knew the whole story. He didn’t want anything bad to happen to his customers.”

The Turk's 'Version' of New Idea's Sales Program

Johnson Tractor’s Leo Johnson still chuckles about the Turk’s days as a New Idea dealer. Back in those days, New Idea shipped a load of manure spreaders to dealers who had to assemble the sides to the floor, the floor to the axle, and then install the aprons. So there was a fair amount of assembly, and most dealers hired a two-man crew to set up these spreaders, he says.

"Well, the Turk would buy them by the semi-load and sell them at a minimum markup, telling the customer he had to come get it and set it up themselves. This infuriated a lot of New Idea dealers. New Idea pushed back on the Turk for advertising low prices and not setting up the spreaders himself. And I am not sure if they terminated him or if he told them to go to hell and then they terminated him. It was one of the two.

“My dad told me that shortly after the Turk was terminated by New Idea, he took out a full page ad in the local papers with a headline of ‘New Idea Cancels the Turk Because He Sells Too Cheap.’ So he used this as a marketing ploy to get farmers to pay attention to everything else he had to sell,” says Johnson.

“The Turk figured out the ‘we sell for less’ concept long before Sam Walton and Walmart did. Many decades earlier, he was doing the same thing in the farm equipment business.”

Steve Voda of Janesville, Wis., says his family bought equipment from the Turk for 3 generations and still rents land from the family trust to this day. Voda recalls getting his hands on one of the Turk’s 100-hour tractors after they’d gotten through the cannery season and bought an Oliver plow and other implements from him. “It was a great program for us farmers,” he says. “He got us a reasonable alternative to buying brand new but just slightly off-warranty.”

The leasing, says Johnson, was extremely rare at the time, and specifically with the canning companies. Others tried it later, but you couldn’t get in later when the interest rates of the 1980s were so high.

“The Turk,” he says, “made a buck and saved a buck. He may have used bank financing at some point in his life, but I don't think there was much of it. He blew everybody away with leasing.”

Unique Business Approach

Johnson recalls how the Turk made it all happen with virtually no overhead; he wanted no more employees than he had to have and personally worked his butt off.

"He operated from a tiny building with just one full-time parts person and a couple of mechanics, and one of them also took on the role of shop foreman, service manager and road technician. Talk about a lean staff.

"He didn’t care much about retailing but, man, did he love ordering, leasing and selling the used units to jockeys. He used jockeys in reverse from most dealers, which was buying units the jockeys found at farm sales. For him, the jockeys were his salesforce and that’s how he kept his overhead so low."

His independence or “maverick nature” is evident in a story Johnson and others recalled about his tangles with New Idea. “He got into a big pissing match with them,” says Johnson.

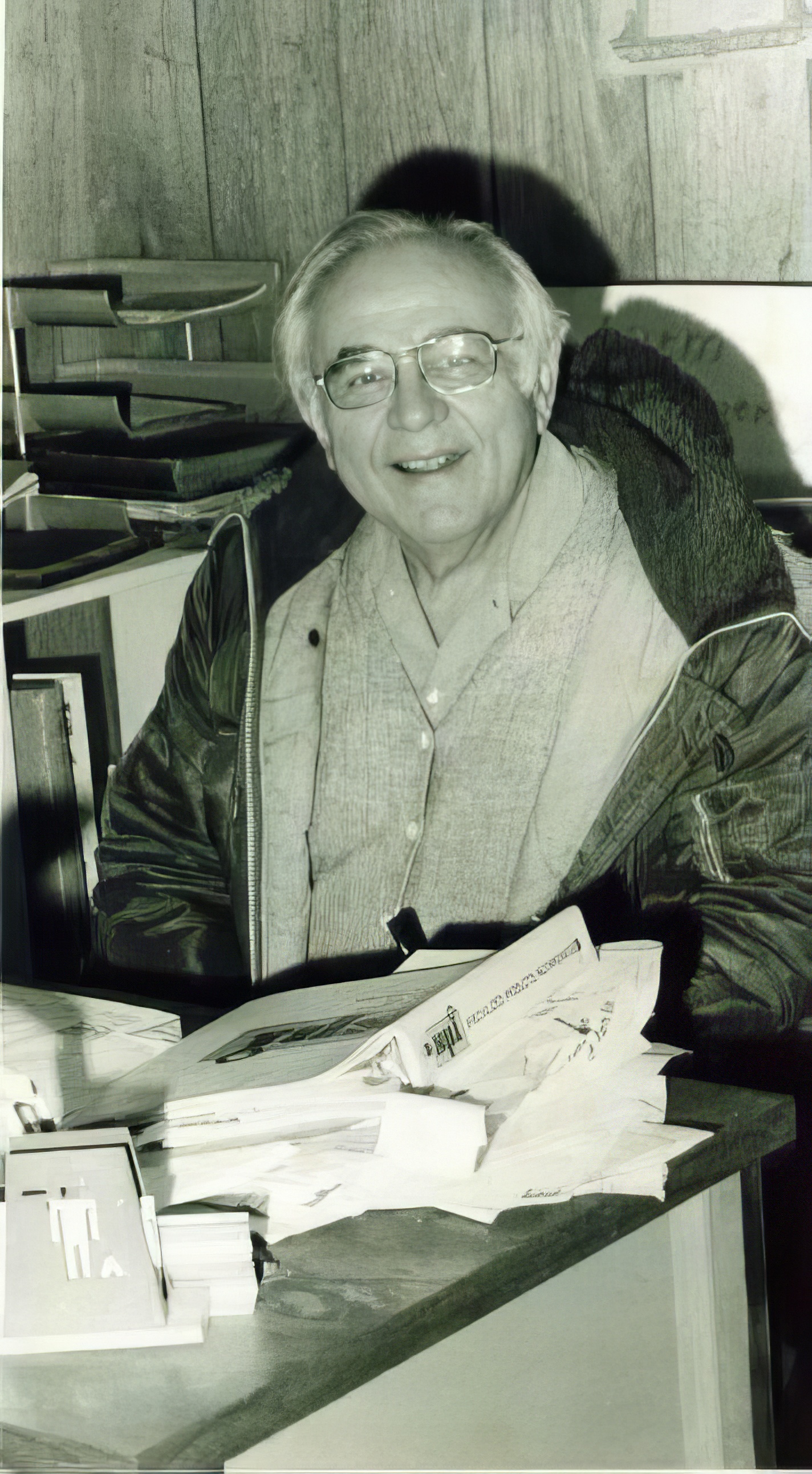

Orhan Yirmibesh Slideshow

Photos courtesy of Sevim Larsen, the Clinton Historical Society and www.newspapers.com.

Influence on Others

When asked about the Turk’s influence, Johnson recalled a personal story. “I personally learned not to be afraid to ask for the order. And not to worry about embarrassing yourself in front of a farmer by asking too many questions or wanting clarification. He knew how to find the solution for them.”

Voda credits the Turk for blazing a trail for the high-volume dealers that would follow. “It was unusual at that time for sure. He was the first to take on that many tractors and turn them multiple times for customers in the 1960s-70s.”

He also recalls the Turk’s office, whose walls were proudly covered with high-volume sales plaques from all the implement companies he carried.

"He discounted well and much more than anyone to get the sale, which he could do because he was so high volume."

While he wasn’t popular, Voda says he was a pioneer of high volume, deep-discount dealerships.

But the Turk apparently knew what he was doing. He’d lease the same tractor to 3 different parties in a year, and then heavily discounted the units for sale at the end. Other dealers caught up with the high volume trend, which later would be inevitable and rule the business. "But the Turk was the first around here to think of it,” he says.

Adds Rieckers: “He influenced other dealers by showing what you could buy at big quantities and paying cash to control all the deals yourself. He was the best there ever was at that from what I’ve heard.”

Others' Personal Memories of the Turk

Below are some additional thoughts from recent interviews as well as commentary found on some industry message boards and YouTube, including the Clinton Historical Society’s social media postings of Tom Larsen’s January research.

“The story goes like this. While in Madison, the Turk meets Ruth, the daughter of a very prominent attorney, bank board director and mayor of Columbus, Wis., named Herbert Zeidler who was not at all impressed with the Turk, and actually went to the point of advising his daughter to find somebody else. Ruth had a pretty strong will as did their daughter, eventually. But they got married and a decade or a couple decades later, and the Turk is a millionaire. He'd done very, very well in the farm equipment business, and had investments all over the place. And anytime he saw Ruth's mom and dad, he always reminded them about various things that he had just bought or various things that he just sold, or a profit that he made on this or that. He liked to rub it in.”

– Leo Johnson, who grew up across the street from the Turk’s home in Clinton, Wis.

“My dad was born and raised in Avalon, Wis. He got a new 88 row-crop tractor, and a plow from that gentleman in 1952. Gramma paid cash. Dad wanted a set of cultivators also but didn't have the money. He was watching my dad looking at them. He said, ‘Follow me’ and showed him a used set for a quarter of the price. Still painted. He gave an 18-year-old a great deal.

– Brad Roehl

“The Turk sold $1 million dollars worth of equipment in 65-66 for sure and was a member of Oliver's high 10 club. Just think how many 1650 and 1850s that was when he was ordering 100 tractors at a time. Plus, when Charles City got cute and send them with the wrong tires, he would call them and send the load back – returned freight of course.”

– Tom Wendler

“Everybody I have talked to that knows about the Turk said he was a great guy and they loved to deal with him. He was honest and friendly. There was a story I heard about how an 18-year-old kid was trying to get into farming and no banks would give him a loan, but the Turk gave him an 880 and a plow and said, ‘Pay me when you can.’ The kid had no collateral but didn't worry about it. The Turk financed this young guy wanting to get into farming out his own pocket. He said ‘pay me when you can.’”

– Ross Rieckers, the “Oliver Tractor Man” who became intrigued with the first tractor he’d ever bought and researched the build card. He discovered the Turk and Badger Farm Store through his crazy ads in the back of 1950s and 1960s farm magazines he’d purchased.

“We still have a 1755 Oliver my grandpa bought from the Turk as a canning company lease return.”

– Jacob Bobolz

“I spent many an hour hanging around the Turk's dealership in Clinton. Seems like he and Dad were both headstrong hagglers. Dad never had a bad word to say about the Turk. The Turk would lease loads of tractors to the Green Giant company in Belvidere, Ill., then sell them after the lease to local farmers. The tractors were fine but lots of times the PTO would not disengage right because the plates in the clutches got warped from getting slipped by the non-farm kid drivers. My brother Denny also worked for the Turk putting together the Badger Air compressors (a sideline business that the Turk assembled and shipped all over the place)."

– Jim Franseen

“The Turk was a respected businessman; shrewd but very fair. He was a genuine friend to all his customers. We did business with him for many years. I remember nephew Matt in high school.”

– Timothy Kitzman

“He helped a lot of farmers in the area get started farming.”

– Mitchell Robert Buchanan

“He hired the first woman parts department person in the county. Sevim and Eric Larsen, who ran the parts department, were moving to California and I was hired as his replacement. And as they say, the rest is history.”

— Lorene Kitzman

“I worked for him after school in the store, stocking, taking inventory and parts, and on Saturdays assembled air compressors and made manure spreader aprons $1.25 an hour, He wanted me to work for him full time after I graduated high-school, but my father insisted that I go on to college.”

— Mike Strohbusch

Personality

How do you describe the Turk? Here’s some phrases that we found.

Charisma coming out of his ears … Creative thinker who could sell you on his ideas … True entrepreneur … Great mind for business … Larger than life … Consummate deal-maker and competitor who liked to win … Master Promoter ... Called it like he saw it.

“He was the kind of guy that could go up and talk to anybody, even in his heavy Turkish accent in somewhat broken English, " says Johnson. “But that didn't stop him. He never worried what other people thought. He did his own thing, figured out a way to make money, and just put the pedal to the metal when opportunities existed.”

Clinton farmer Bob Wildermuth described the Turk as “flamboyant and a friend to everyone." He adds that he "sold more Olivers than anyone in the state of Wisconsin, and there are still a lot in this area that the Turk brought in.”

Voda laughed about his trademark belly dancers and how the Turk was the only one whose Christmas parties included that style of entertainment. "He’d always be there encouraging us to dance and get our pictures in the paper.”

Johnson sums up the colorful figure with a story from his boyhood. “His downtown store was the first time I'd ever seen a snowmobile when I was 11 or 12. He always had a jab for me like, "You know if you were my boy, you'd already have one of these by now."

Sevim sums up his personality as “one who didn’t do things the American way. He never totally assimilated to American culture. He was a character, a maverick and very outspoken.”

All Good Things Come to An End

He started from humble beginnings and amassed a significant fortune in his lifetime. Johnson recalls the Turk’s father-in-law had disapproved of him for Ruth’s suitor. As the story goes, even decades later, the Turk was quick to wave his wealth and accomplishments under his father-in-law’s nose.

Voda adds that while the Turk never farmed himself, he started buying farms as an investment. In fact, Voda still farms land owned by the Yirmibesh family trust.

And while it was not the export business that he once dreamt of, along the way he started shipping used-up tractors to Turkey, other Mediterranean countries and Eastern Europe, says Johnson. “I was in Turkey on a Wisconsin Rural Leadership tour and we saw his Olivers still running that he’d sent from the U.S.”

Memories of Orhan Yirmibesh, 'The Turk'

Editor’s Note: Charlie Dee reached out to Farm Equipment offices after seeing the first-ever Farm Equipment Dealer Hall of Fame, which included a posthumous honor of Orhan Yirmibesh, also know as “The Turk.” The Turk was a trend-setter in many ways, and Dee explains below the impact that the immigrant dealer Yirmibesh had on a new dealer-principal.

As a young new farm equipment dealer in Northeast Iowa with many smaller farms, our dealership had a need for good used farm equipment. So we started to purchase lease return tractors from a couple of dealerships in Wisconsin.

One of those dealers was “The Truk” Orhan Yirmibesh, in Clinton Wis. My wife, Donna, and I would go to visit the Turk and she would stay and visit his wife, Ruth, while Orhan and I would go to his dealership. I would purchase some of his lease-return tractors.

We became good friends and even stayed overnight with Orhan and Ruth occasionally in Delavan Wis., as we purchased the lease-return tractors.

I grew up in the farm equipment business but wanted nothing to do with it when I got out of high school. But after getting married in 1969 my father’s health were failing, and my wife and I had to decide whether to go into the farm equipment business or not. At that time, I was working in the engineering department at Trane Co., the air conditioning manufacturer. So, we returned to New Albin, Iowa, and formed a partnership with my father, Clinton Dee.

Of course, with young energy, we had lots of ideas how to grow the farm business, and one of them was selling good used lease-return tractors, which we purchased in Wisconsin.

During one visit with Orhan, he encouraged me to consider leasing equipment to canning companies. When I returned to Iowa, I searched out regional canning companies and found a few that I contacted. The canning companies in our area had some interest and wanted more information.

As I was new and didn’t know how to make a contract with them, Orhan graciously offered to help by using a contract template he had. So, Donna and I started a company called Dee Leasing Service Inc. to manage the new business venture. Everything was going well, and we signed a lease for 5 Oliver 1555 tractors with Galesville Canning Co. in Galesville, Wis. During those years there was a shortage of farm equipment, and it was on an allocation basis, so I was unable to get the 5 Oliver 1555s from the factory. Of course I was discouraged after putting out the effort to get the business started. Orhan again helped by giving me 5 of his allocated tractors and he would retain 5 he had previously leased and release them another season.

We became good business friends to the point Orhan suggested I sell my dealership in New Albin, Iowa, and join in partnership with him. We even discussed how that would look. But Donna and I had committed to my father when we moved back to New Albin, so I decided to remain and grow the New Albin, Iowa, dealership. We’d eventually add Waukon and Decorah, Iowa, to our dealership locations.

Dee Implement has become a dealership that thinks creatively in developing new business ventures in the international markets and leasing equipment to canning companies and seed corn companies and growers. Orhan’s example of thinking “outside the box” has had a great impact on our business development.

Wallem recalls that the Turk wanted to exit the still-thriving business due to his wife’s poor health and offered him a great deal with generous 10-year terms that he should have taken.

Sevim recalls that as her dad thought about retiring, he, his tractor man John Reinhart and mechanic and right-hand man Jim Delaney ("a fun Irishman with a keen sense of humor who balanced out the Turk and was the backbone of the repair operation," she says) recruited her husband Eric, who had returned from serving in Vietnam, to join them. As a result, they moved from their home in California back to Wisconsin.

“Those three got along fine but my dad was too controlling and critical of every move they made so they disbanded. We moved back to Sacramento for Eric to attend law school in 1972 and the store was sold shortly after that.”

After retiring, Turk and Ruth moved to Palm Desert, Calif., where Sevim and her husband Eric resided so they could be near their granddaughter, Erica.

Related Content: Memories of Orhan Yirmibesh, 'The Turk'

Check out more from the Dealer Hall of Fame Class of 2024:

- Ronald D. Offutt, RDO Equipment, Fargo, N.D.

- Cleve Buttars, Agri-Service, Kimberly, Idaho

- Charlie Hoober, Hoober Inc., Intercourse, Pa.

- Paul Wallem, Wallem International, Belvidere, Ill, & Central Sands International, Plainfield, Wis.

- David Meyer and Peter Christianson, Titan Machinery, Fargo, N.D.

- Ferenc (1932-2017) & Tom Rosztoczy, Avondale, Ariz.

- Earl Livingston, Livingston Machinery (Parallel Ag), Chickasha, Okla.

- Orhan Yirmibesh, Badger Farm Store, Clinton & Avalon, Wis.

- Derek Stimson, Rocky Mountain Equipment, Calgary, Alta.

Read Farm Equipment's Inaugural Hall of Fame

Nominate a Future Farm Equipment Dealer Hall of Famer

Submit a nomination for the next class! The Farm Equipment Dealer Hall of Fame recognizes the achievements of individuals who excelled in farm equipment dealer retail sales & service.