Properly used irrigated acres are roughly twice as productive as dryland fields, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, but only 20% of the world’s cropland is irrigated.

FAO says in order to meet rising global demand for food and fiber, more and more farmland will have to be irrigated, and that irrigation must be as efficient as possible to limit the impact on natural resources.

The U.S. Great Plains produces the bulk of grain and fiber crops, with a significant portion of that coming from irrigated agriculture, a business that finds itself increasingly affected by falling aquifer levels and increased water-use regulation. Still, variable-rate technology and improved soil moisture monitoring are surfacing as keys to the continued viability and growth of watered crops in the U.S.

“Over the next 10 years, we will really see an increase in the number of growers using variable rate irrigation (VRI). I don’t think we have come close to hitting the full market potential,” says Cole Frederick, Valley Irrigation’s product manager of VRI technology.

Center pivot sprinklers such as this Valley unit equipped with LEPA drops and nozzles can match drip irrigation systems in efficiency for pumped water applied to the crop. Some High Plains growers are finding doubling the number of LEPA drops on the system can enhance water use efficiency even further. Center pivot sprinklers such as this Valley unit equipped with LEPA drops and nozzles can match drip irrigation systems in efficiency for pumped water applied to the crop. Some High Plains growers are finding doubling the number of LEPA drops on the system can enhance water use efficiency even further.

|

“Many more farmers will be investing in this technology, especially with water use restrictions increasing and the continuous growth from producers to maximize their yields with the inputs (water) they are investing in.” Also, improvements in VRI undoubtedly will improve precision in chemigation and fertigation applications.

Several of the major sprinkler manufacturers offer VRI options, including Lindsay Corp., which has fielded a proprietary package in the U.S., Australia and New Zealand that boasts extremely “high resolution” accuracy.

“Our product is more flexible because its software uses more zones, allowing more precise control of the sprinkler nozzles according to mapping data inputs,” says Dirk Lenie, Lindsay’s vice president of global marketing. The more accurately the sprinklers are turned on and off, the less water has to be pumped to efficiently maintain the proper amount of moisture in the root zone of the crop, he explains.

That soil, crop and water interaction is the key to future gains in efficiencies, adds Frederick. “As we learn more about those interactions, that knowledge can be applied to VRI software. We will see VRI becoming even more efficient when it combines soil moisture monitoring, weather conditions, and additional data such as soil types, fertility levels, field slope, etc.”

Valley recently entered into a collaborative agreement with AquaSpy to offer farmers advanced soil moisture monitoring technology with the Valley SoilPro 1200. The system uses a dozen sensors in a field from root zone down to 60 inches and provides real-time data to tell the grower how much water is needed at each stage of a crop’s growth cycle. Sold as an annual subscription service, the technology allows irrigation decisions to be made based on when and where crop inputs are needed to maximize yields.

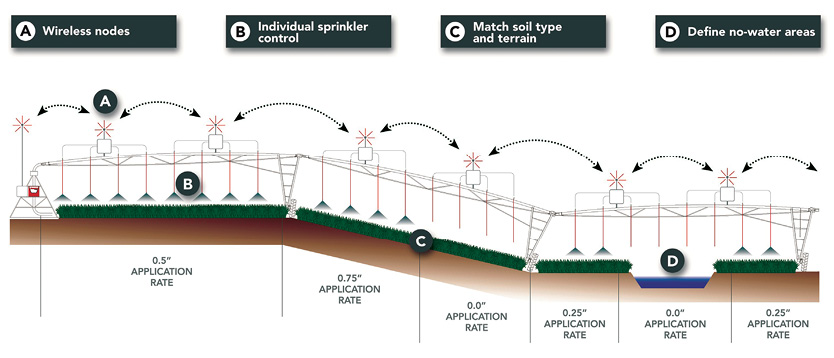

This VRI system uses wireless nodes controlling up to 4 valves to turn sprinkler nozzles on and off in Lindsay’s Pinpoint Plan. The nodes also act as repeaters, sending signals up and down the length of the pivot. This VRI system uses wireless nodes controlling up to 4 valves to turn sprinkler nozzles on and off in Lindsay’s Pinpoint Plan. The nodes also act as repeaters, sending signals up and down the length of the pivot.

|

Lenie says the next step in VRI development likely will be the integration of VRI packages into control systems such as Lindsay’s FieldNET system, to allow producers to control their VRI systems remotely. “As it is currently, you have to go to the field to make changes or download data for regulatory reports,” he explains.

Sprinkler Efficiency

Increases in sprinkler efficiency over the next 10 years likely will come in small increments, since a low-pressure sprinkler system equipped with low energy precision application (LEPA) drops and nozzles are already 93-95% efficient at applying pumped water to the crop.

“That compares with drip,” says Lenie. “The question is can we get people to switch out of flood irrigation and to get sprinkler users to give up their end guns — particularly in areas where water is plentiful. Most efficiencies have been made for sprinklers — which make up 50% of the irrigation systems in the U.S. — unless you consider working with droplet size and nozzle design,” he explains.

Also, Lindsay introduced a new solid-state magnetic water flow meter in April to work with its FieldNET sprinkler control and data collection program. “This tool will help producers provide regulators with very accurate records of water applied,” Lenie explains.

At Valley, Rich Panowicz, vice president for North American sales agrees, noting efficiency improvements will come in systems management, and watering to maintain moisture at the root zone, not allowing it to extend below that zone and be wasted. “Also, sprinkler systems must be properly designed, installed and maintained for their particular field situations to attain and maintain their efficiencies,” he says.

Collaboration Cuts Water Use

As pumping costs climb and water tables drop, irrigation companies and hybrid breeders are looking to one another in a collaborative effort to reduce the amount of water used to grow crops.

Available in the U.S., New Zealand and Australia, Lindsay’s precision VRI allows for variable application of water according to soil type and slope, as well as no-water “void zones” to avoid irrigating ravines and other non-productive areas in a field. |

Syngenta and Lindsay Corp. are collaborating on a case study — Water + Intelligent Irrigation Platform — that includes Syngenta’s crop genetics, traits, crop protection inputs and agronomic advice with Lindsay’s irrigation technology and equipment.

“Working with Syngenta’s more drought-resistant plants and new hybrid seeds, we’ll be putting soil moisture sensors with pivots for better water use,” Lenie explains.

“It’s in both parties’ interest to come up with more efficient crop production, and in this way we can provide the farmers tools to ensure they get the most from the available technology.”

Lindsay officials say the program is designed to enable farmers to maintain their irrigated land and maximum yields while reducing water use by up to 25%.

Reducing Energy Use in Irrigation

Innovation and new technology across the U.S. Great Plains are showing some growers substantial reductions in energy use and significant gains in water efficiency.

In pumping, the use of “written pole” motors is making electric pumping plants up to 100 horsepower available to growers who are unable to get — or afford — 3-phase electric power. The motors, when tied to variable frequency drives (VFD) make irrigation available to growers with single-phase electrical systems who otherwise would not have had electricity as an option.

VFD technology also is instrumental in cutting electrical costs on standard 3-phase systems, as well as allowing some growers to begin powering their irrigation pumps with privately owned generator sets dedicated to their irrigation wells. In some cases, in the Texas Panhandle gen-set irrigation fueled with natural gas provides substantial savings over buying power from the local co-op, even after the initial cost of the generators.

Also, there’s a move, where soils permit, toward doubling the number of drops on LEPA (low energy precision application) sprinklers and slowing the system to water crops more efficiently in a single pass. Experience with this technique in the High Plains, which grew out of the citrus farming practices in Arizona, has shown significant boosts in water efficiency are possible.