Establishing a basic labor budget has countless advantages for dealers looking to get the most out of their service shops. While it takes upfront planning, the payoff can be huge in terms of making sure the service team stays focused on billable hours vs. non-revenue hours, throughout the year.

That’s according to Kelly Mathison, a management consultant for the Western Equipment Dealers Assn. (WEDA) Dealer Institute and founder of Kayzen Management, a consulting and training company. To help dealers get started, he’s created an easy-to-understand formula for creating a labor budget, and offers some sound advice on how to achieve your labor sales goals.

For most dealers, service sales are a significant contributor to total dealership sales, with labor sales bringing in the highest gross margins. “Service sales quite often are more than 10% of the total dealership sales,” notes Mathison. “So there's a lot of pressure to make sure we're covering all those costs for technicians, as well as creating profitability.”

Then there’s the cost of your dealership’s service department: it's significant, and there are a lot of hidden costs. “A labor budget forces you to look not only at your contribution back to the dealership, but quite often whether you’re delivering the highest gross margin to the dealership,” says Mathison. “So it forces you to look at your labor as inventory, not just as an expense or just wages.”

Dealer Takeaways

- Work to limit technicians non-revenue time

- Service managers should proactively manage the workflow

- Keep track with a scorecard to help communicate efficiency to the service technicians

Labor as Inventory

Because labor wages are one of the largest costs for the service department, it’s important to look at labor as inventory. From there, dealers can create weekly, monthly, quarterly and annual targets, as with parts or wholegoods inventory.

When viewing labor as inventory, it’s important to note that labor inventory is time. Unlike product inventory, it has no shelf life and not every hour is billable. For example, a full-time tech gets paid for 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, but factor in things like vacations, holidays, training days and sick days, and it’s closer to 1,800 available hours each year — an immediate loss of 280 hours.

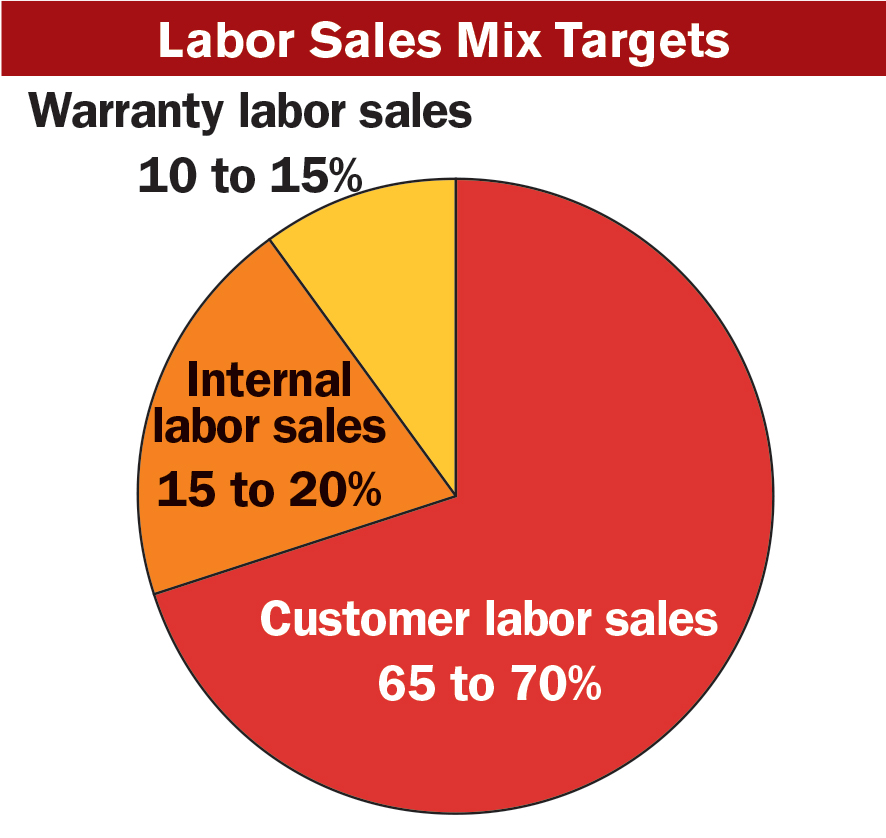

Then there’s the difference between time that produces revenue — customer labor, internal setup and pre-delivery work, trade reconditioning, warranty, and paid product improvement programs such as recalls — and non-revenue hours spent on things like general shop repair and maintenance, servicing company vehicles, “busy work”, and the usual delays and interruptions.

Mathison advises service managers to make every effort to find and assign technicians to revenue jobs vs. non-revenue “busy work” that often happens in between jobs, early in the day while work is getting organized, or late in the day when there isn’t time to start another major job. “That's all non-revenue or lost time, meaning there's nobody writing a check for that time,” he says.

Recognizing there’s a limited number of available hours, and there’s a difference between hours that produce revenue and those that do not, dealers need to make sure they’re getting the maximum number of billable hours from their technicians. Proper time management is critical.

Establish a Productivity Target

Productivity is one of the best measurements service managers can use to ensure technicians are working on revenue-producing jobs when they are available. It’s calculated by dividing the revenue hours by the 8 available hours. For example, if a technician clocks 8 hours a day, but bills 6.5 hours of revenue work orders, then his productivity is calculated at 6.5 divided by 8, or 81.25%.

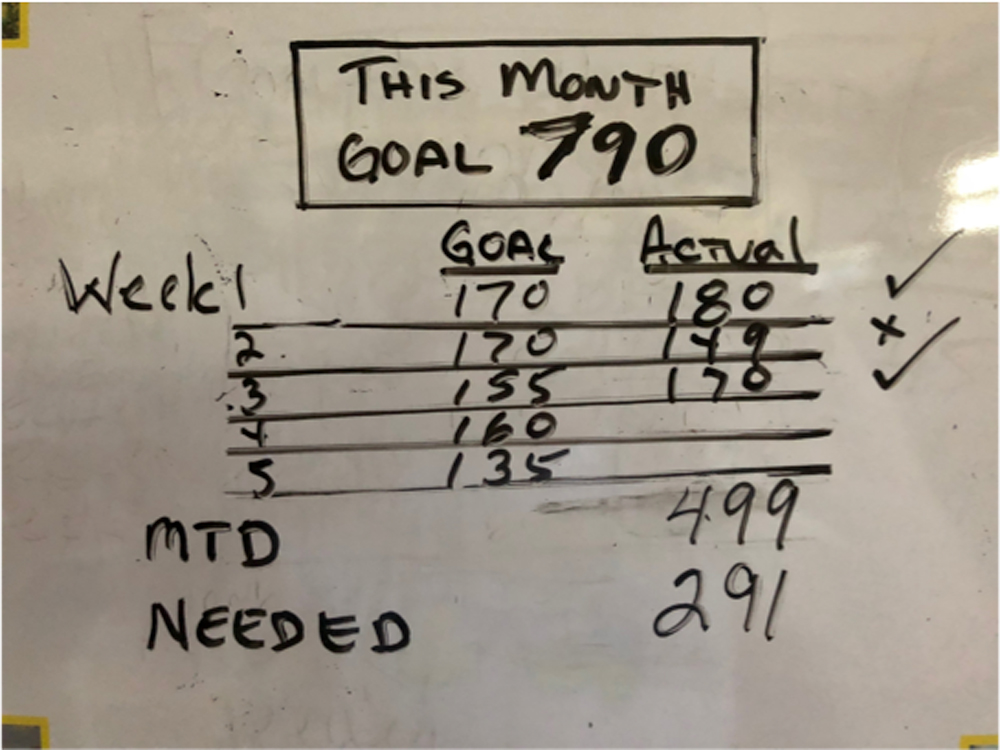

This simple but effective scorecard, prominently placed near the shop entrance, lets the team know how much they have billed for the week, and what’s required to achieve the monthly goal.

“We realize we have delays, we have interruptions and we have times where the technician might be talking to a customer or waiting for instructions from a manager, or breaks,” says Mathison. “You can't charge every minute of his day out.”

So for most dealers, a good productivity target for the service shop is 85% — a goal that can be factored into a basic labor budget, he says. For each technician, allocate 1,800 available hours, multiply that by 85%, and you can achieve a total of 1,530 available hours per technician per year.

Set Target for Labor Revenue

Once dealers understand the total available hours per technician per year, it’s easy to calculate projected revenue:

- 85% productivity (1,800 available hours x .85) = 1,530 x 6 Techs = 9,180 revenue hours

- Revenue hours x shop rate (9,180 x $110) = $1,009,800 in annual revenue, before expense

“What kind of revenue should you be generating from labor sales? This is a great place to start,” says Mathison. “It’s very conservative, but it's a great way to get your head around what it really means to set a target for labor.”

Consider Your Shop Rate

When setting your target revenue, a key consideration is your shop rate. “A lot of shops look at a wage multiple of 3-4 times your average tech wage,” says Mathison. “So if your average tech wage is $30 an hour, then you may have a shop rate of somewhere between $105 and $120 an hour.

“Of course you've got to be competitive. But if you're going to drive positive margins, you also have to be in line with your inventory cost.”

Last, dealers need to deduct the cost of sales — the technicians’ wages, benefits and other department expenses — to understand the true profit picture. That said, if the dealer’s shop rate is $110 an hour and the cost of the sale is $30, the gross margin comes in at $80 for every revenue hour.

Budget for Income & Revenue Hours

When budgeting from a financial perspective, the accounting department will want a labor budget that specifies labor revenue for every week, month and quarter. “To a technician or a service manager, you may be saying, ‘It's a lot easier to explain to my technicians how many hours I have to sell,’” notes Mathison.

To translate, simply multiply the total revenue hours by the shop rate, and divide by 52 weeks to come up with how many revenue hours your dealership needs to bill for every week or month. To take it back to the shop, divide the monthly or weekly total revenue hours by the number of technicians to come up with a weekly or monthly target for billable hours for each technician.

Support Revenue Goals with a Service Marketing Plan

Dealers can support their labor revenue goals with a service marketing plan that brings in retail service work — inspection programs, proactive maintenance programs, maintenance contracts with customers — so there’s always a steady stream of revenue work coming in.

Value-added service programs are another good way to generate seasonal retail service work, Mathison says. For example, when seasonal requirements change, the service team can prepare lawn and garden equipment for snow removal by replacing mowers and tillers with snow-removal attachments.

“Whether it's cotton pickers or combines, forge harvesters or balers, or sprayer winterization programs, by doing value-added service programs post season, your customers will be ready to go the next season,” says Mathison. “We all know there are lots of opportunities there.”

“A labor budget forces you to look not only at your contribution back to the dealership, but quite often whether you’re delivering the highest gross margin to the dealership…”

These programs can also be reflected in the labor budget. For example, if tractor inspections are running on average 5 hours, and generate another 20-30 hours of repairs, the service manager can determine how many inspections he needs to sell throughout the year.

“Look for patterns,” suggests Mathison. “We all realize that not every work order is going to be exactly the same, but an experienced service manager is going to have a pretty good feel for those averages.”

Hit Your Labor Budget

Once the dealership’s labor goals have been set, Mathison advises the following:

Set goals and track progress. Once dealers have determined how many hours each technician needs to hit every week and every month, set up a scorecard to track the team’s progress against those targets. Just like on a sports team, it’s important to know what the score is, and how much time is remaining in the game: Is the team going to hit its goals by the end of the week? By the end of the month? A scorecard will help everyone stay on track. From a scorecard that pops up on everybody's screen in the morning, to a whiteboard that’s prominently displayed outside the service manager's office, visibility is the key to making sure everyone understands and is engaged.

Use a single time-card system. Dealerships should have a single time-card system for technicians that logs hours worked as well as hours spent on revenue work orders, as opposed to two separate systems. This way, when technicians punch in, they know immediately what they will be working on. It’s the service manager’s responsibility to have revenue jobs lined up prior to the start of the day, so when the technicians come in, they clock right onto a revenue work order.

Monitor progress and have revenue jobs lined up. Instead of waiting for technicians to seek assistance, monitor activities in the service shop and proactively ask: “Do you have enough work for the day? Is everything lined up? Have the parts arrived?” When parts aren’t available, or customer information is missing, service managers can manage around these delays by having a second and third job lined up. If it’s just a short delay, assign a small job. The key is to anticipate delays and be proactive.

Appoint a “non-revenue” worker to reduce wait times for technicians. In situations where technicians are losing time by going to the yard, finding a machine, removing snow and ice, and bringing units into the shop, consider hiring a “non-revenue” assistant or yard person who can help service technicians work more efficiently.

Reduce or eliminate causes for delays. Technicians can easily lose 15-20 minutes while looking for tools if the tool room isn't organized. They can also lose time waiting for parts at the parts counter. Dealers need to keep tool rooms organized, and enlist the help of the parts team. Instead of having technicians pick parts, they can hand over a parts diagram with the items they need highlighted, so the parts people can locate the parts, put them in a box, and deliver them to the technician. Remind the parts team: for every dollar's worth of labor sold, a dollar's worth of parts is sold.

Require approval for non-revenue jobs. This tip came directly from a service manager, and it’s had a huge impact on his dealership, Mathison says. Quite simply, he does not allow technicians to log onto a non-revenue job without his approval: It’s the service manager who approves when a technician works on a repair, does maintenance, goes to training, or any other delay code.

A thoughtful labor budget is a critically important step in the service budgeting process: it serves not only as an essential tool for forecasting revenue and expenses, it also acts as a roadmap and scorecard that allows management to set clearly defined targets and measure results.

“For managers, it creates a roadmap that makes you realize what you have to hit as you're going down that path,” says Mathison. “It also allows you to set goals and targets along the way, to ensure you're on track. So it really shows all these very insightful steps as we go along the path.

“Hitting your labor budget is really around goal setting,” Mathison concludes. “Goal setting and tracking is your first step.”

Related Content:

Creating and Hitting a Basic Labor Budget for your Dealership Service Department [Webinar]

Top Tips to Get Your Service Department Performing at Its Highest

Building Customer Loyalty Through Quality Service, Not Low Prices

Getting Tech Savvy in the Service Department