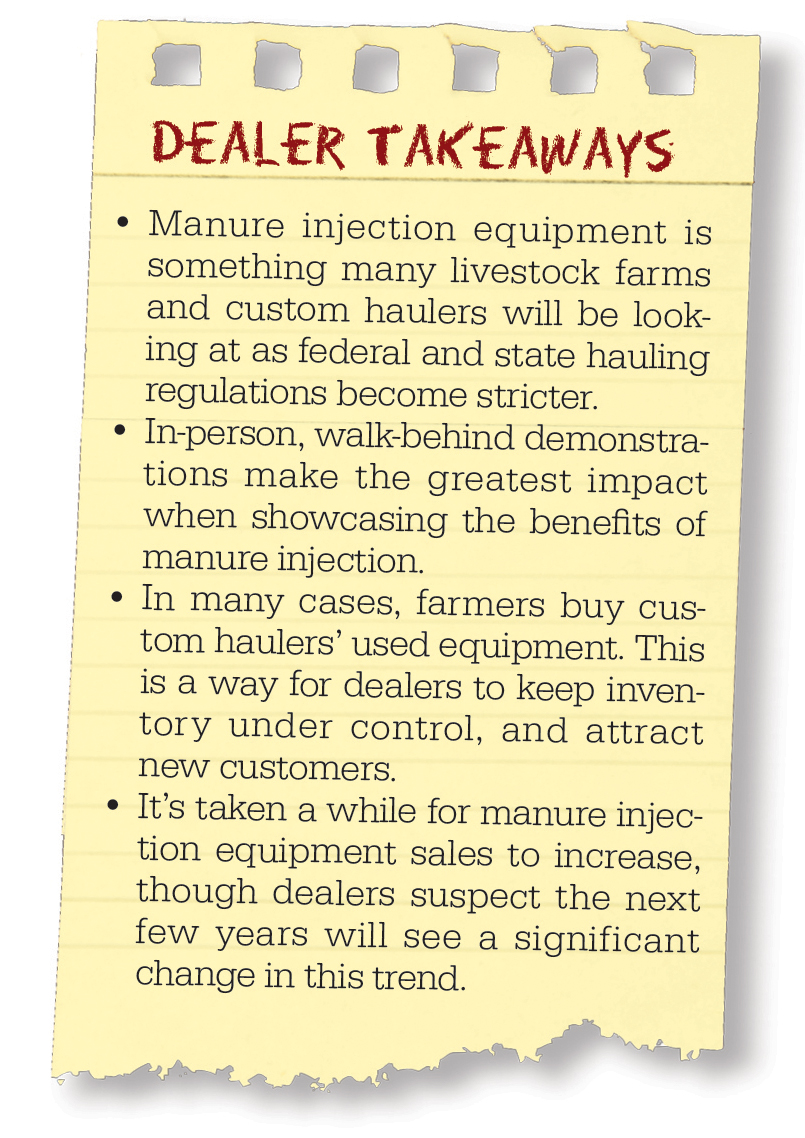

There is change in the air and it smells as strong as freshly spread manure on a windy day. State and federal regulations are pushing farmers to look at new ways of spreading manure and equipment dealers say injection is one alternative that producers are adopting to work with the new regulations and to be better neighbors.

It’s no secret the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to push for stricter waste regulations for farms. A dairy with more than 700 cows is currently designated as a concentrated animal feeding operation which has the potential to discharge pollution into surface water. For that reason, each farm must apply for a “National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System” (NPDES) permit from its individual state, as well as develop and implement a “Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan” (CNMP).

Seven hundred head is the magic number for dairy, but manure regulations exist for all animal types. A farmer with 2,500 swine weighing more than 55 pounds is required to file the same paperwork, as must one with 30,000 laying hens or broilers. In the case of poultry, the manner of manure handling (liquid or solid) also determines the regulatory numbers.

Each state then boasts its own manure regulations, especially involving spreading on open fields and the months of the year the practice is allowed. The bottom line is that manure runoff is in the news, and will continue to be so, says John George, Jr., president of Jag Pumps and Application Equipment in St. Charles, Iowa. Jag offers its customer the Hydro Engineering manure injection equipment.

Gary Fennig is the owner of Fennig Equipment in Coldwater, Ohio, which has sold the Yetter Manufacturing Avenger line of injection equipment for 15 years. He says it used to be that bigger facilities were the only ones considering the use of manure injection equipment, but today water runoff issues are pushing others to adopt the practice as well.

Randy Brynsaas sells VTI equipment from his dealership, Brynsaas Sales and Service Inc. in Decorah, Iowa. He says the manure industry has changed a lot in the last 15 years, and that large hog and dairy operations in Iowa are making the state’s Dept. of Natural Resources re-evaluate runoff regulations. Detailed guidelines tell haulers where, when and what manure can be applied throughout the year. These are important for a dealership to understand on a basic level when discussing injection equipment, as knowledge and helping a customer map their business plan is only another sales tool.

Another downside of manure is odor, and manure injection equipment helps farmers be more desirable neighbors. Odor management plans have become standard practice, and farmers are asked by their state governments for information including: type of application equipment (broadcast, knife inject, sweep inject, etc.), timing of manure applications, location of applications and distance to neighbors and agitation procedure. Direct manure injection is a strategic way farmers can keep those plans painless and complaints to a minimum.

Benefits of Injection

Hydro Engineering teamed with California State Univ., Fresno, to conduct studies over several years, comparing flood irrigation to direct injection methods, George says. Forty-acre test plots of each were evaluated side by side, and the results were game changers for the industry. California as a whole has been slower to adopt the injection system, and this is a mystery to those involved especially since farmers can harvest as many as three crops in a given year. The weather allows for intense agricultural production, more than in the Midwest, and the innate benefit of manure has proven to be substantial.

George notes that the tests consistently revealed farmers were able to get by with less water on the injected fields, those crops handled stress much better and also produced a higher yield compared to the flood irrigation areas. He says the plants absorbed organic material easier, and yields increased 15-20% on the injected plots. George emphasizes that the ability to apply agronomic-grade fertilizer through manure alone is a win-win situation. “You just emptied your pit, put material on the field, saved on anhydrous ammonia and increased production,” he says.

Fennig explains that the heavy regulations being developed regarding runoff into the Chesapeake Bay watershed are likely to affect the Midwest sooner than later. The watershed region’s 87,000 farms are primarily livestock operations, producing approximately 44 million tons of manure each year. Manure injection equipment is considered a best practice in that 6-state area to alleviate runoff concerns and maintain compliance with its stricter policy.

“Why not use what’s available?” George asks his customers. “It’s free, you need to get rid of it and keep within compliance anyway.”

Catching on With Farmers

Direct manure injection can help customers keep runoff issues and odor complaints to a minimum. |

Brynsaas and George concur with Fennig that initially the manure injection systems were bought by custom haulers who used 12 or 16 foot chisel machines. These manure businessmen were looking for a larger tool bar as the pits became deeper and the application standards lighter. Since custom haulers are usually paid per gallon, the faster the application, the more profit they see coming in. George says a 180 horsepower pump was large when the equipment first appeared on the market, and today the machines are running on 500 horsepower.

These few manure haulers, however, became overloaded with the increasing size of livestock operations. As a result, individual farmers started buying their own equipment, often the used injectors the custom haulers were trading in each year. Brynsaas says the sales of manure injection equipment were slow at first, maybe one unit a year. This was 5 years ago when coulter till units came on the scene. Last year, Brynsaas says he sold 8 units to farmers and deals with about 30 custom operators, of which only a handful have switched to direct injection methods.

Fennig says a few of his customers use liquid manure in sidedress and are seeing advantages with that application method. He says sales still haven’t gone gangbusters and buyers look closely at the benefit provided by the significant investment needed to start a manure injection program. He says allowing customers to ask questions opens the door to a meaningful conversation, long-term relationship and sales. That, and helping them understand manure regulations as well as environmental benefits of injection, are vital to success. Fennig notes that manure management is here to stay and it’s at the top of every farmer’s priority list if they have livestock. “Open up any farm magazine and the two topics being discussed today are cover crops and water quality,” he notes. Fennig says he sold about 30 Avenger units this past year, an average of three or four per toolbar.

To reach potential customers, Brynsaas says that he does quite a bit of advertising, in national farm publications and online, but that age-old word of mouth is still the most effective. “It’s been that way in farming for 100 years,” he says. “If you can get one sold in a neighborhood, the others see it working and want to keep up.”

Best Prospects: Young Farmers

Fennig admits getting farmers to change is the biggest challenge. The older generation wants to hang onto the way things have always been done. Brynsaas adds that the younger generation is traditionally driving the purchases of manure injection equipment. “Normally dad has the money and the kids have the ideas,” he says.

The fathers are also better at finding good used equipment, when the kids want the “Cadillacs,” he explains. Brynsaas says with the increasing availability of used equipment, there are ways to make both happy.

Fennig agrees, and notes the younger generation has been raised talking about water quality and runoff effects. He says price is one thing, but change is 90% of the hurdle in selling this equipment. “Every farmer wants to do what’s best for the land,” he says. “They want the land to be passed from generation to generation. They know what’s right and if they want to keep the land, this is something they’ll have to do.”

This parent/child dynamic helps when a dealer such as George is selling a manure injection system, because he says he can base the information on facts, not assumptions. This is what the older generation wants to hear first and foremost, anyway: the actual return on investment.

George says he doesn’t use a sales pitch, per say, but stresses that each equipment purchase is unique to the customer. The system is designed to meet individual needs, he explains, citing application rate, distance and obstacles in getting from the lagoon to the field as things he takes into consideration when working with clients.

Rating the Return

“The customer first of all has to realize that the initial investment is doing the right thing for the land,” says Fennig when discussing return on investment. For example, his local service area was facing runoff issues in a local lake, and the growth of confinement livestock operations were being held accountable. Manure haulers needed to find a new way of approaching this task.

Dealers then needed to help their customers justify the cost of transitioning to manure injection. For larger, custom manure haulers, this is easier than for the smaller farms. Brynsaas says if a farmer can hire someone for $10,000 a year to haul manure, it’s hard to justify the $125,000 cost for a new tank spreader with coulter till.

George explains, however, that if a farmer is pumping 800 or 1,000 gallons per minute, buying a used manure injection applicator at about 75% of the cost of a new one would suffice for what the farmer needs to do, It becomes a different story for a farmer with 2-3 million gallons of manure to haul each year. This is about the amount of manure where he sees a change in purchasing decisions.

Some custom haulers, he adds, are hauling as many as 150 million gallons a year. George says that if a custom operation is using five spreaders this year, and the cost is $20,000 to upgrade each for the next season, it may be a better option to transition to a direct injector. While the cost could come to $500,000 ($100,000 each), the payoff in the long term is worth it.

The manure hauler’s customers may be pushing for the change too, and George says many are. “They have to stay updated or they start losing business,” Brynsaas adds.

Brynsaas says one of the biggest benefits of manure injection equipment is the farmer’s ultimate control on when and where manure is hauled. The “when” is the key point here, and something he finds difficult to place a price on. “If a custom hauler comes in and it’s too wet, you don’t want him applying it on your fields, it might be a while before he can come back,” he explains. “The farmer has much more control with his own equipment.”

The return on production varies by the nitrogen availability in various types of manure and facilities where it’s stored. Hog application rates, George says, can range from 3,000-20,000 gallons per acre, based on the type of facility, and in a dairy operations, 8,000-18,000 gallons per acre is not unusual. Brynsaas says that customers have reported 8 bushels an acre gain in soybean fields, simply by using injection equipment.

The Virginia Cooperative Extension’s research shows that the benefit of injecting manure is definitely measurable. If N is estimated at $0.70/pound, the value of injected manure is $4.20/1,000 gallons. A recent report explains that if an 8,000 gallon typical dairy slurry is applied to an acre, injection will lead to an extra 48 pounds N/acre, which is about a $33.60 value. If a farmer injects 500,000 gallons of dairy manure, the increased value of this N would be about $2,100. (Rory Maguire and Timothy Woodward, 2010).

All three dealers agree that the return takes time to reveal itself, at least a few years. George says dealers must realize what a customer needs to have in place to pay the bills and make a profit. Brynsaas agrees, noting that the return will be unique for each individual customer, and suggests that farmers should be bringing their numbers to the dealer for review.

“Manure use to be a waste product people wanted to get rid of,” he adds. Today, a farmer with 900 head of pigs tells him that underneath the herd lies $25,000 of natural fertilizer. This equates to dollars that don’t have to be given to the co-op, Brynsaas explains.

Walk Behind Demos

George says that at the start, Jag hosted quite a few demonstrations, both in the Midwest and California. “It took a while for people to absorb what we were doing, but once that happened, it produced a snowball effect.”

Fennig saw the same trend, and says that as time goes by, more people are asking about manure injection benefits. In northwest Ohio, Mercer County’s Manure Days have proven a successful platform for him to showcase the benefits.

Brynsaas explains that letting the buyers walk behind and see it work makes a difference. He says that dealers should not be afraid to try something new. For example, he let three custom manure haulers run some acres through a VTI injector, and the next year, all three bought their own.

“Once you get a few machines out there, the neighbors see them and with some talk at the feed mills, they start to sell themselves,” he says.

Even before a customer walks into a dealership, chances are they’ve checked out the product online. The Internet has become a resource the dealerships can rely on. George says that when Jag first began its tenure, the World Wide Web was unheard of. “Now, a guy can sit in his office and watch this all happen on YouTube,” he says.

Brynsaas says the Internet is great, but walking alongside an injector while it’s working is always better. He also admits he’s not the first guy to sell any newly introduced piece of equipment. He likes to let the manufacturer work the bugs out the first year, and then offer it when the changes have been made. That said, he also realizes things will always change, and something new and improved will be on the lots next year. He still keeps his customer’s best interest in mind and helps find the equipment that best suits them.

George advises dealers to do their research first before acquiring any injection equipment lines. He says it’s important to look at the distance from the dealership to customers, and develop a general idea of what could be sold, but also how it will be moved.

The social aspect extends beyond marketing and into service, from both the dealer and manufacturer. George says that especially in abnormal seasons, when manure must be hauled in a very tight timeframe, those hauling are looking for exceptional support. “When these guys are out there pumping and have a problem, they want someone they can get in touch with — now,” he says.

He recommends going with a manufacturer that is versatile, but also listens to its dealers. George says that as a dealer, and custom manure operation owner, he sees both sides of the sale.

“The dealers are out there doing this, they know what the actual customer needs are,” he explains. “Everything I sell, I use myself.”

Fennig says promoting is a big part of manure injection equipment sales. The customer still has a choice of what to do, and where to buy it. Many farmers eventually realize his sales pitch was really not a pitch at all, but the truth. “Once I convince them it will do exactly what I said, that’s when I have repeat business,” he says.

The practice of letting the customer lead the way also contributes to trust in the dealership, something that as more manure regulations are imposed on farmers will be of utmost importance, Fennig says.