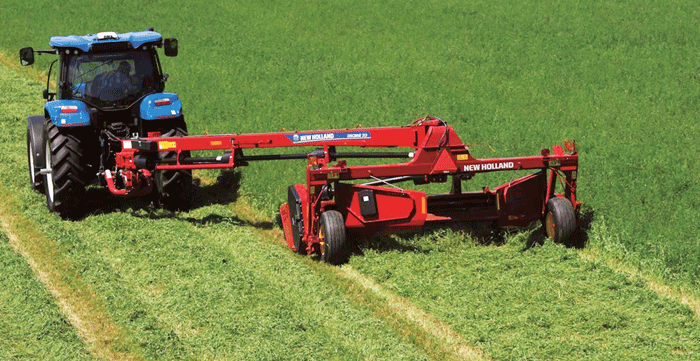

Pictured Above: Large trailed mowers have been introduced to lay a wide swath of hay the full width of the cutter bar. Researchers have demonstrated how wide swathing helps to speed drydown, which improves overall forage quality.

Photo Courtesy of Vermeer Corp.

In June 2003, Tom Kilcer and his New York Extension Service colleagues tested their wide swath hay-in-a-day concept by putting it to a test in a soggy alfalfa field after an overnight shower dropped 0.033 inches of rain and left the meadow soaked with free-standing water.

“We mowed at 11 a.m., and in less than 8 hours from the first cutting we had haylage without moving the swath,” Kilcer recalls. “For several years similar tests confirmed laying down swaths of 80% of the cutter bar width would allow natural photosynthesis that occurs after cutting to quickly dry the material to nearly 60% moisture levels.”

Kilcer’s tests at that time with a New Holland disc mower-conditioner showed increasing swath width on high moisture crops such as brown mid-rib sorghum sudan dramatically increased the drying rate, with the best performance shown at a 94% swath width produced by a sidebar mower with no conditioning.

“We made the statement that, for silage, swath width was more important than conditioning, and that still holds true. For baled hay material, however, conditioning is necessary as moisture levels need to drop below the 60% level,” he says.

In addition to the obvious savings in time and labor, the process also improved forage quality by reducing field losses and improving the efficiency of getting forage out of the field in a timely manner. Still, the process was somewhat of a local phenomenon in upstate New York. Old production methods die hard, and little hay equipment of the early-to-mid 2000s would accommodate wide swath haying.

Equipment like this basket rake was developed to combine two windrows of hay to produce a swath with a working width of up to 30 feet, which helps to facilitate the wide swath approach for speeding drydown.

Photo Courtesy of Rankin Equipment

Fifteen years later, Kilcer, a certified crop consultant and owner of Advanced Ag Systems, says the process is much more widely accepted, not only in the northeast dairy region, but in hay meadows across the country.

“Also, the equipment makers are on board with mowers that will provide the 75-90% swath width necessary for successful hay-in-a-day. Vermeer, Kuhn, New Holland, Gehl and Deere are all building wide-swath models,” Kilcer notes. “I know our work threw a grenade in the hay machinery business, but growers who use it today will tell you it was worth it,” Kilcer muses.

“I recently visited with a large farmer in western New York, who told me the wide swathing and ‘haylage in a day’ boosted his annual profitability by six figures. Another grower with a 100-head organic dairy in Minnesota told me the practice cut his annual grain costs by $109,500.

“Fifteen years later, hay-in-a-day is working from New England to Ohio and westward as far as Idaho,” he adds.

Fine Tuning the Process

With wide swath haying becoming more common, Kilcer says there are still tweaks producers can make to improve it further. “The big issue I’m seeing is the amount of dirt people are putting in their feed,” he explains. “Many producers are running their mowers too close to the ground where blades lift dirt into the forage and that is costing them money.

“A large part of this begins at the dealership,” Kilcer says. “Many times sales reps set up a new machine to mow flush with the ground because it looks cleaner and better than the old ‘brand X’ machine they are replacing.”

Wide-swath haying has come into its own as a best management practice for quick drying haylage. This H7230 Discbine mower-conditioner is an example of equipment built around the practice and features the ability to provide a swath 100% of its cutting width. Research indicates the most efficient drying occurs with 80% or greater swath widths.

Photo Courtesy of New Holland

Kilcer says forage analyses show ash levels of 6-7% in plant material alone, but with the incorporation of field dirt, those levels can rise to the 9-11% range.

“Over that 2 percentage-point spread, Dr. Charles Sniffin of Fencrest LLC consulting found milk production can drop up to 1.9 pounds of milk per cow per day,” he says. “Multiplied by the number of cows times 365 days and you have shocking numbers. Losses of $60,000-$70,000 per farm is not unusual.

“Some of this is unavoidable, but the major reason is mowing too closely. Some growers have their machines set to mow barely an inch off the surface where the blades will hit bumps and gouge out field irregularities,” he explains. “We’re recommending cutting alfalfa at 3-3.5 inches and grass at 4 inches. This allows for standing stubble to catch the swath and improve air circulation, as well as providing cleaner forage.”

Cutting grasses at 4 inches provides cleaner hay, and also helps improve stand longevity and total yield. Kilcer says because grasses don’t grow from growing points but from photosynthetic leaf area, mowing too closely — where the mowed area looks brown — slows regrowth and stresses the plant. “Some research shows a 50% stand loss from regularly mowing under 4 inches,” he explains.

What to Avoid

Another practice Kilcer says is adding dirt to forage is the use of tipped blades on mowers. “Tipped blades act like propellers or mulching blades on a lawn mower. They lift dirt and field residue into the forage stream. For the cleanest forage, we recommend using flat blades. We are not looking for ‘minimum tillage’ haylage,” he jokes.

In addition to the obvious savings in time and labor, wid swathing also improves forage quality by reducing field losses and speeding the process of getting forage out of the field in a timely manner.

Photo Courtesy of Vermeer Corp.

Also, Kilcer says the common practice of lowering deflector shields on mowers to achieve a wide swath is counter-productive.

“While studying methods to successfully make same-day haylage from hard-to-harvest red clover, we found heavy first-cutting clover balled into wet lumps on deflectors which were designed to widen the mower’s swath. The lumps dropped into the swath and their presence brought the overall drying rate of the wider swath back to the levels of a non-wide windrow,” he says. “The higher quality of forage, the worse this happens.

“Where we removed the shields to let the forage flow through and disperse unimpeded, the swath had uniform density and dried faster and more evenly.”

Another lesson 15 years of practicing hay-in-a-day has revealed is the negatives of running tine conditioners on alfalfa. “It’s the wrong thing to do,” Kilcer explains. “Tines strip alfalfa leaves and cost you feed.

“We used to think physically drying alfalfa hay was enough, but the photosynthetic process is very important. In the presence of sunlight, leaves continue to respire and use water to produce sugars and starches, and they do this at a rapid rate. We’ve found this accounts for the majority of drying and, if you don’t damage the leaves, photosynthesis and capillary action will pull moisture levels below 60% very quickly if alfalfa is cut and laid on the ground in wide swaths.

“We’re consistently getting this done without conditioning in a matter of several hours after cutting, just by swathing at 80-90% of the cutter bar width.”

Hay Drying 101

Dealers who want to sharpen their knowledge of haying should understand the basics of dry-down to better understand their customers’ needs when it comes to selecting the proper mower for their operation.

“If we understand and use the biology of forage drying properly, hay dries faster and has less chance of being rained on, and that means the total digestible nutrients (TDN) of the harvested forage is higher,” says Dan Undersander, University of Wisconsin extension forage agronomist.

That “biology” is the use of post-cutting photosynthesis to naturally consume plant moisture in a natural curing phase.

“Forage is typically at 75-80% moisture when it’s cut and must be at 60-65% for haylage and 14-18% or lower for baling,” Undersander explains. “To reach the haylage harvest stage, the hay must go through Phase I curing, which can be accomplished with a wide-swath mower.”

In Phase I, drying takes place when the cut hay continues to photosynthesize and lose moisture through the stomates in the leaf. Stomates open in daylight and close in darkness, and that’s why hay laid in a wide swath in the sun will dry faster.

Undersander says once haylage has gone through Phase I, it’s ready for the chopper. If the forage is destined for baling, however, it must go through Phases II and III curing before harvest. Conditioning alfalfa and alfalfa-grass blends assures faster dry-down for baling.

Phase II of the drying process involves continued moisture loss from the stem and leaf surface (even though stomates have closed). “At this phase, conditioning increases drying rate, especially at the lower end of the moisture content,” Undersander explains. “

In Phase III, tightly-held water in the stems evaporate,” he says. “Conditioning breaks stems and allows more opportunity for water loss because little water loss will occur through the waxy cuticle of the stem.”