Boots that slid and trudged through endless mud in 2011 found themselves forlornly stirring up plumes of dust with every step taken in rain-starved fields just a short year later.

Brad Brown is a wearer of just such a pair of boots and he’s of the opinion that unpredictable weather is the new normal.

“When I was growing up, the weather was the same all the time, now it seems to bounce from one extreme to the other,” the Center Point, Ind., farmer says. “As farmers, we have to adapt to conserve and manage moisture no matter if there’s too much or too little.”

A good portion of Brown’s contemporaries seem to agree. Two hundred and eleven of 313 farmers — 67% — responding to a survey on weather confirmed they believe weather is becoming more volatile. The survey was conducted by No-Till Farmer, a sister publication of Farm Equipment during the week of August 6.

Their observations and concerns are well founded, according to Elwynn Taylor, Iowa State Univ. extension climatologist. In his evaluation of about 150 years of yield records, he has identified hints of a weather cycle impacting crop yields.

“We’ve found a run of years with consistent yields and then a period of highly volatile yields. The pattern is 25 years of volatility followed by about 19 years of consistency. This cycle has happened three times and we’re in the fourth cycle now,” Taylor says.

His study of the annual growth rates of Midwest tree rings further confirms his weather cycles theory.

“We don’t know why there is this pattern, but it exists and has existed for 800 years, according to the tree ring record. This is a long-standing pattern, at least in human terms,” he says.

For example, Taylor notes that consistent crop yields were recorded from 1956 through 1973 and were capped with disaster in 1974. There was a late frost, drought and an early frost in the fall resulting in very low yields.

“It was the beginning of 25 years of volatility. We saw droughts in 1983 and 1988 and floods in 1993 along with record-high yield years during that period. One that stood out was 1979; it was a banner year,” he says. “Then we went through a time of consistent yields from 1996 to the present. Now we’re due to enter the 25 years of erratic yields. Some good, some bad and a few that are average.”

It’s as simple as that. Farmers can just start crossing off the years until the next cycle when consistent weather comes around. Except things are never that simple.

Weather and climate are complex, interactive systems that must be viewed through a variety of filters to see the full picture. Those filters include temperature, rainfall events, overall rainfall, weather cycles and climate cycles to name a few.

Warming Up

Global warming. It exists, it doesn’t exist, the data is faulty, the polar icecaps are melting, the polar icecaps are building, global warming is natural, industrialization is causing it, we’re making it worse, it’s a disaster that must be stopped, it’s ideal for us as a species — opinions are polarized (no pun intended), passionate and each point of view is backed by a different set of experts and data.

Elwynn Taylor of Iowa State Univ., says, “We’ve found there are a run of years with consistent yields and a period of highly volatile yields. The pattern is 25 years of volatility followed by about 19 years of consistency. This cycle has happened three times and we’re in the fourth cycle now.”

Those who believe in the disasterous impact of global warming certainly got some fuel for their fire in 2012.

More than 15,000 warm temperature records were broken during the month of March, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Climatic Data Center. And as summer progressed, the heat continued to build as if an aging grandparent was left in charge of the thermostat.

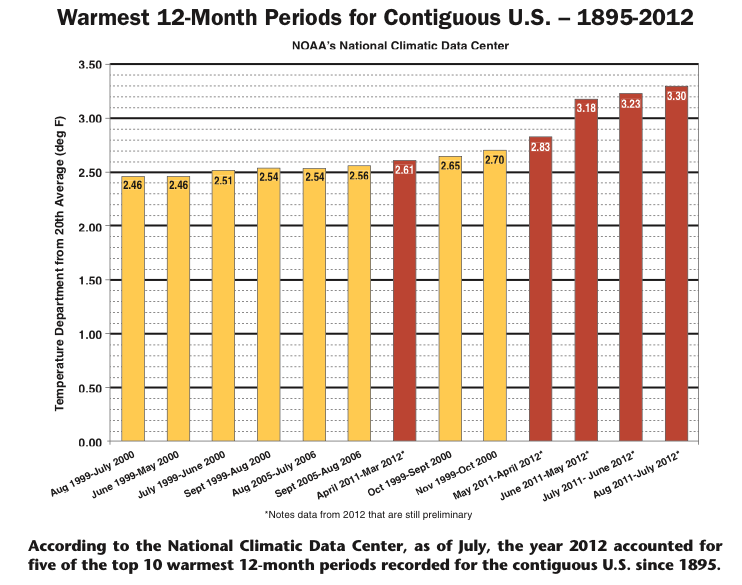

As of July, the year 2012 accounted for five of the top 10 warmest 12-month periods recorded for the contiguous U.S. since 1895.

Dennis Avery, director of the Hudson Institute’s Center for Global Food Issues, agrees that, by and large, the earth has been warming since around 1710. The difference is — he doesn’t believe it’s a bad thing and he doesn’t think the warming will be dramatic.

He notes that Greenland ice cores are able to provide 150,000 years of temperature data not only revealed the expected ice ages, but a secondary cycle between the ice ages that show a 2–4 degree oscillation in the earth’s temperature every 750 years. The same interglacial trends were noted in North Atlantic sediment cores and Antarctic ice cores.

“Since the last ice age we have experienced seven intense cold periods and seven global warmings,” Avery says. And when he lines up those cooling and warming periods with recorded human history, he comes to another interesting conclusion.

“Annual precipitation hasn’t changed as much as the seasonality of precipitation ... ”

“Global warmings have been the good times for humans, animals and vegetables,” he says. “The ‘Little Ice Ages’ have been desperately bad. That’s when you get shorter, cloudier growing seasons, earlier frosts and violent floods.”

He notes a Chinese researcher, Zhibin Zhang, has examined the voluminous Chinese records of the last 1,000 years and says 80% of wars, rebellions and collapsed dynasties have occurred during these Little Ice Ages.

“Our study suggests that food production during the last two millennia has been more unstable during cooler periods, resulting in more social conflicts owing to rebellions within the dynasties or/and southward aggressions from northern pastoral nomadic societies in ancient China.”

“We’re in a warming trend and ought to be damned glad,” Avery says. “The next Little Ice Age is 300 years away.”

He notes that within the 1,500 year-long up and down temperature cycles is another 30-year pattern of temperature ups and downs.

“The earth has been cooling slightly since 2007. It also cooled slightly for 30 years after 1940. But, despite the ups and downs, the net result has been a moderate long warming,” says Avery.

These 30-year variations he attributes to shifts in Pacific Ocean currents known as Pacific Oscillation. Based on this concept, he believes that — despite the record temperatures set this past summer — the nation is in for another 25 years of slight cooling before warming again.

“There was a 0.5 degree increase in temperature between 1900 and 2000. I expect a total of one degree in long-term warming, maybe 1.5 degrees,” Avery says. “That doesn’t push anybody very hard. What you’re getting is more crop production from Northern China and Canada.”

, David Wolfe, who studies climate change effects on agriculture at Cornell Univ., and some of his contemporaries aren’t convinced that the warming will be mild and follow the historical pattern.

“Many climate scientists are concerned that these natural cycles are being, and will continue to be, swamped out by a much more dramatic warming — as much as 6-12 degrees Fahrenheit this century — associated with the increase in greenhouse gases,” Wolfe says.

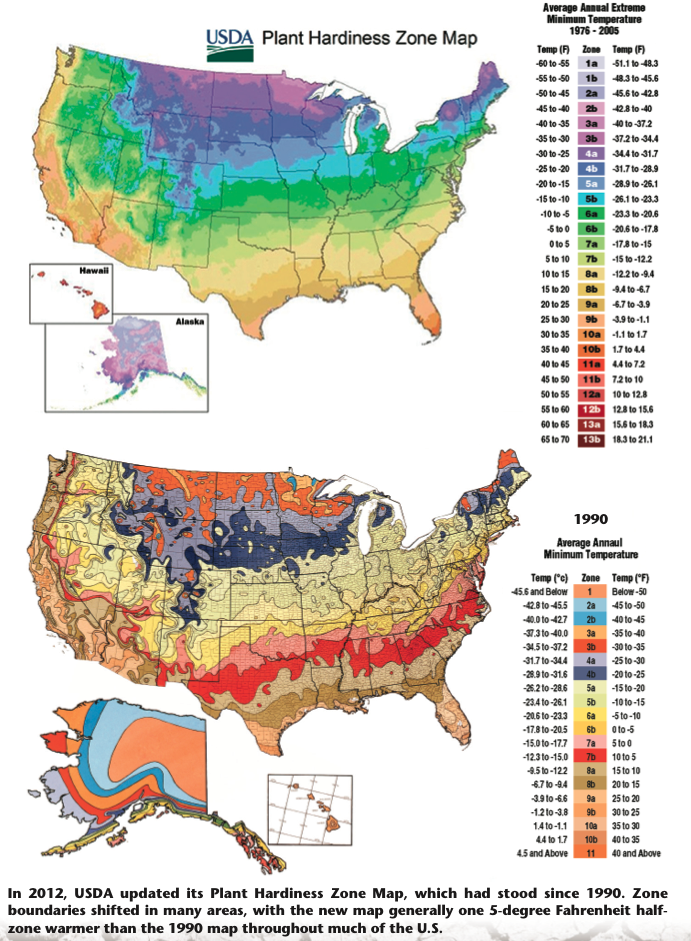

Production of crops such as corn and soybeans has shifted slightly north with warming temperatures and improved hybrids and varieties. In 2012, USDA updated its Plant Hardiness Zone Map, which had stood since 1990.

Zone boundaries have shifted in many areas, with the new map generally one 5-degree Fahrenheit half-zone warmer than the 1990 map throughout much of the U.S., according to the USDA release. The changes aren’t cut and dried indications of climate change, though.

They cite a combination of more sophisticated methods for mapping zones between weather stations and the new ability to factor in changes of elevation, nearness to large bodies of water, position on terrain and the addition of more weather station data.

Sweating Nighttime Temps

Continuing increases in nighttime temperatures are more concerning than variable daytime highs, says Jerry Hatfield, laboratory director and supervisory plant physiologist for the National Lab for Ag and the Environment.

“An interesting piece of the overall puzzle of global temperatures rising is that it’s the minimum temperatures, such as nighttime temperatures, that are increasing more than the maximum temperatures,” he explains. “From the plant and animal perspective, the minimum temperatures are often much more important than the maximum temperatures.”

According to most industry observers, 2012 will be one of the most difficult farm- ing years experienced in the last three decades, with some comparing current conditions with the 1988 drought, which in itself was the worst drought since the Great Depression. Photo courtesy of John Deere

NOAA reports that between 1950 and 1993, nighttime daily minimum air temperatures over land increased by about 0.2 degrees centigrade per decade. The change has lengthened the freeze-free season in many mid- and high-latitude regions, they say.

Just like a refrigerator keeps fruit fresh longer by slowing development, cool evening temperatures slow and control the metabolism of plants and animals as well.

“Corn grows quickly when it’s warm at night because it’s putting a lot of energy into growth and cell expansion,” Hatfield says. “The plant tends to go through the life cycle more quickly, reducing yield.”

Taylor says producers saw the effect of warm nights in 2011.

“People were surprised last year because for as good as the corn looked it yielded less than they thought. That was due to warm nights,” he says.

Hatfield sees this warming as a potential driver for changing crops grown in certain regions.

“If increasing heat is hitting the southern part of the Corn Belt during pollination, which impacts yield, it may force movement northward and replace corn with crops that have a different seasonal water use and pollination pattern,” he says.

Shifting Precipitation

Despite the drought, the problem isn’t actually the lack of rain, it’s when and how the rain comes.

“Annual precipitation hasn’t changed as much as the seasonality of precipitation,” Hatfield says. “We’re seeing more rainfall at the beginning of the year and less during the overall growing season.”

Those rainfalls also are larger and more intense, which can mean flooding. And in areas like Iowa, which have actually seen an overall increase in rainfall, the result is rivers out of their banks multiple times per year.

Iowa has seen a 10% overall increase in precipitation since 1950. And, the number of rainy days per year has doubled in recent years as compared to when the weather stations were installed 120 years ago, Taylor says.

“The problem is that 10% more precipitation doubles the amount of water going down the streams,” he says.

Why? Because a corn crop only needs 25 inches of rainfall to produce a record crop, and the soil can only hold about 10 inches of water at a time, he explains. Anything above those amounts goes down the river.

“Farmers were amazed in 2002 because they got record crops with dry streams and low rivers. That’s because they got 25 inches of moisture spread out over the course of the year,” Taylor says. “There wasn’t a drop left to go downstream.

“The dry years are still dry, but the wet years are wetter than usual shifting us in the direction of an increase in the frequency of flooding throughout the Midwest.”

Dust Bowl Fears

Any time there is a drought and heat, attention is drawn back to the hardship of the Dust Bowl, or other tough years like 1988.

“This year is not as harsh of a drought as 1988,” Taylor says. “The heat stress is only about a third of what it was then and we’re just not in the ballpark of the droughts of the 1950s or the Dust Bowl.”

Looking at the weather cycles, Taylor predicts the worst year for crops in the 2000s is still coming.

“The worst years in the last 800 years have averaged 89 years apart. The worst year for the Midwest was 1847, the next worst year was 1936 and the upcoming one will be 2025 if the weather keeps doing what it has done for the last 800 years,” he says.

Increasing intensity in the 25-year volatility cycles may also be a concern. Taylor says they tend to go up in intensity for three cycles and then are less intense for three cycles.

“The intensity on this cycle should be going up as compared to the previous two cycles, one of which included the Dust Bowl,” he says. “Anything we’ve been doing on risk management since 1993 is just practice, now comes reality as we expect volatility for the next 25 years.”