Farm equipment dealers who are looking to establish a succession plan for their companies to ensure their dealerships remain viable business entities, whether or not they remain at the helm of the company, are taking a close look at the potential role that an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) could play in the process.

According to a panel of three dealership executives with ESOP experience, the reasons to consider an ESOP include:

- To reward dealership employees

- No one loses their job if someone dies

- Peace of mind for customers and equipment suppliers

- Ownership can cash out of the business without retiring or leaving

- Owners can exit the business on their own schedule

If organized and operated properly, the panelists also agree that ESOPs can lead to other “positives” for the dealership. Among these are establishing an “ownership mentality” among employees while providing them with a better retirement. And, as Shawn Skaggs of Livingston Machinery pointed out, “A better retirement plan equals better employee recruitment.”

The panelists included Clint Schnoor, president of Agri-Service, based in Idaho; Ronnie Barnett, CFO, H&R Agri-Power, headquartered in Kentucky; and Shawn Skaggs, COO of Livingston Machinery Co. of Oklahoma.

ESOPs: Not a Succession Plan

Schnoor emphasized that an ESOP is not a succession plan, as such. “An ESOP is an ownership structure,” he says. At the same time, ESOPs can be an integral part of a formal succession plan, providing the framework for management succession, while giving a dealership direction and focus for the future.

According to the National Center for Employee Ownership (NCEO), about two-thirds of ESOPs are used to provide a market for the shares of a departing owner of a profitable, closely held company. Most of the others are used either as a supplemental employee benefit plan or as a means to borrow money in a tax-favored manner. The organization says there are currently about 7,000 ESOPs that cover about 13.5 million employees.

From l to r are Clint Schnoor, Agri-Service; Shawn Skaggs, Livingston Machinery; and Ronnie Barnett, H&R Agri-Power.

Establishing an ESOP is a “fun process,” says Schnoor, and it can take place as one major transaction, as was the case with Livingston Machinery and Agri-Service. Or, as it was the case with H&R Agri-Power, the full-blown ESOP was established over a period of years — increasing from a 2.6% stake in 2007 to a 100% ESOP in 2014.

Before this can take place, the dealership must typically perform its due diligence to determine if an ESOP is the correct approach for the business, says Schnoor. “Number one is to conduct a feasibility study to make sure that this kind of entity structure makes sense. An ESOP is based around an employee’s stock ownership plan, which is a qualified retirement plan. If you don’t have enough employees in your company, the math just doesn’t work. You should have an experienced financial advisor or an accountant with experience in ESOPs work with you on this.”

Schnoor explains that establishing the ESOP is much like setting up a 401k plan or other qualified retirement plan, and usually involves a trust document.

NCEO describes the process this way: companies set up a trust fund for employees and contribute either cash to buy company stock, contribute shares directly to the plan, or have the plan borrow money to buy shares. If the plan borrows money, the company makes contributions to the plan to enable it to repay the loan. Contributions to the plan are tax-deductible. Employees pay no tax on the contributions until they receive the stock when they leave or retire. They then either sell it on the market or back to the company.

Provided that an ESOP owns 30% or more of company stock and the company is a C-Corporation, owners of a private firm selling to an ESOP can defer taxation on their gains by reinvesting in securities of other companies. S-Corporations can have ESOPs as well. Earnings attributable to the ESOP’s ownership share in S-Corporations are not taxable.

Putting ESOPs to Work

Clint Schnoor, President Agri-Service

Founded: 1990 by Cleve Buttars

Operations: 12 store locations in Idaho, Oregon and Utah

Est. Annual Revenues: $120 million

ESOP Background: Set up ESOP Trust in 2009 and became a 100% S-Corp owned ESOP in 2010. At the time, company had8 locations with 140 employees. Company adopted an “open-book” management approach in 2010 and formed an ESOP committee comprised of employees in 2011. The company went through an asset sale in 2013 that required a vote by all ESOP participants, with 98% approving of the sale to a private equity firm. Today, the company has grown to 235 employees in 12 locations.

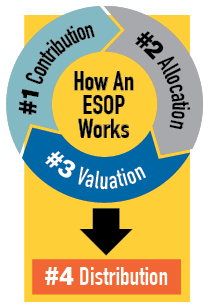

According to the panelists, there are 4 things that happen once an ESOP is set up. The first is the company makes contributions to the ESOP, either in cash or stock. The contributions are then allocated to the employees; the stock is valued, and then distributed to the plan participants.

“The contributions usually are made annually, but can be made more often,” Barnett of H&R Agri-Power explained. “They can be accrued, which is a nice feature because you can actually get your tax return completed and then accrue the contribution back into the previous year, as long as you do it by the due date of your tax return.”

The company, either through cash or stock, funds the ESOP contributions, and the company’s board of directors determines the amount of the contribution. It is then allocated among the ESOP participants, typically on a pro rata basis based on each of each participant’s salary.

Valuation of the company to determine its worth, thus the value of the stock, is also done upfront as part of the transaction. “This will be ongoing each year,” says Barnett. “You will need to have an independent, qualified firm do this valuation. The Dept. of Labor and Internal Revenue Service govern ESOP Trusts with pretty strict rules, so you want to be sure to use someone who is qualified because it will need to stand up under their scrutiny.”

In terms of participants cashing out of the ESOP, distributions usually occur at retirement, disability or death. “There are rules that can be put into the plan that govern how quickly the distributions will take place after these events. If a vested participant leaves for another reason, they are also entitled to a distribution based on their vested account. Restrictions can be placed on the plan as to when that has to happen, but ultimately the account does belong to the employee,” Barnett explained.

Diversification is another facet of ESOPs that those setting up the plan should be aware of, Barnett adds. “If an employee has been a participant for 10 years and is over 50 years old, he or she has the right to diversify the account into another investment. You must offer this right to the employee. But, of course, the payout is based off the stock value at the time the payout is made,” says Barnett.

Examining Tax Issues

“There are a lot of positive tax implications related to ESOPs that really have had support from both sides of the aisle in Congress,” says Barnett of H&R Agri-Power. “Democrats like ESOPs because they’re pro-employee. Republicans like ESOPs because they’re pro-business. So it’s the best of both worlds.”

One of the tax benefits to an ESOP centers on the fact that it is a stock sale, according to Barnett. “This means the owner who is selling his shares to the ESOP will qualify for capital gains treatment. If it is a leveraged transaction, then you can record that to defer the capital gains over the term of the note using an installment tax method.

“If you are a C-Corporation, you can avoid the capital gains tax on the transaction. If a transaction meets certain criteria, the proceeds from the sale can be rolled over into a qualified replacement property. By doing this, gains on the sale can be deferred. It’s very similar to how the 1031 rules work on land and equipment,” Barnett says.

Shawn Skaggs, COO

Livingston Machinery Co.

Founded: 1987 by Earl and Sharon Livingston

Operations: 5 store locations in Oklahoma and Texas

Est. Annual Sales: $88.7 million (with 4 stores)

ESOP Background: Became 100% ESOP in 2008 and a S-Corp ESOP in 2010. The company currently has about 130 co-owners.

There are other ongoing tax implications, as well. These annual contributions the company makes to the ESOP Trust are tax deductible up to 25% of employee compensation. Barnett explains that, if it was a leveraged transaction, even the principal payments on the loan are tax deductible. “This is a pretty unique thing to be able to not only deduct interest on the loan but also deduct the principal as well.”

Another action that H&R Agri-Power took was to contribute stock to the ESOP Trust, rather than cash. “If you do this, you can deduct the fair market value of the stock,” Barnett explained. “The result is you have a non-cash transaction, but you’re getting a tax benefit at the same time.”

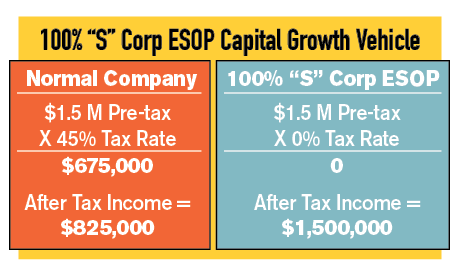

S-Corporations also present opportunities for significant tax benefits, according to Barnett. “In general, S-Corporations do not pay federal income tax. Instead the income flows out to the shareholders and the tax is paid at the shareholder level. The ESOP Trust is an exempt shareholder, so in effect, a 100% S-Corporation ESOP is a tax-exempt entity and there’s a lot of power to this structure.”

ESOP-Acquisition Scenario

The ongoing consolidation of farm equipment dealerships and the hundreds of acquisitions that have taken place during the past decade or more also presents opportunities for ESOP companies, according to Barnett.

“As you’re negotiating an acquisition, usually the buyer wants to structure the deal as an asset purchase where they can deduct the assets as quickly as possible. The seller will usually want it structured as a stock sale where it qualifies for capital gains treatment,” he explains.

For example, if you’re a 100% S-Corporation ESOP, there can be advantages to entering into a stock purchase. In this case, you don’t have to be concerned about the deduction and the seller can get more after tax, according to Barnett. “You can actually negotiate a lower price because on an after-tax basis the seller would end up with more net after tax,” says Barnett. “Obviously, there are other reasons why you may not want to purchase stock because of possible liabilities and things like that, but this approach is certainly something to consider.”

Barnett also discussed the difficulty growing dealerships often have with growing capital fast enough to support their growth and to take advantage of opportunities when they arise. He says that H&R Agri-Power, itself, has struggled with this conundrum.

“You can have a pretty good year, but when you give half of it back by way of taxes, it’s difficult to grow your capital fast enough through earnings to take advantage of the opportunities in the marketplace,” he says.

Ronnie Barnett, CFO H&R Agri-Power

Founded: 1990 by Wayne Hunt

Operations: 14 store locations in Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi and Illinois

Est. Annual Sales: $300 million

ESOP Background: Established in 2007. Owner didn’t want to sell any of his shares, so new shares in the company were issued from 2007-2012. Employee ownership grew to nearly 19% by 2012. By 2014 dealership became a 100% ESOP. Today, the company has about 400 co-owners.

To illustrate, Barnett offers the example at upper left. Under normal conditions, a $50 million company with 3% bottom line profitability generates $1.5 million in profits before tax. After applying a 45% tax rate, it ends up with after-tax income of $825,000. On the other hand, because a 100% S-Corporation ESOP pays no tax, it would have an after-tax income of $1.5 million.

“You can see how powerful this can be as a capital growth vehicle, which enables you to be able to better take advantage of opportunities in the marketplace as they arise,” Barnett adds. Selling the Concept

Clearly, ESOPs offer a range of benefits for the company, but the panelists agree that it’s the employees who are often the toughest sell.

“You have to know up front that this thing isn’t all roses,” says Skaggs of Livingston Machinery. “You have to handle it right. That ‘ownership mentality’ that we want when setting up an ESOP only occurs when you actually treat your employees like owners. If you just treat them the same way that you have every day before and nothing changes, you’re probably not going to get that ownership mentality. You might for a few days, but it’ll wear off, and it might even go the opposite direction.”

Skaggs points out that there’s no doubt that an ESOP can provide a better retirement for employees, but they must understand how the retirement benefit works and how the ESOP works. “It has to be explained regularly that none of it is immediately available until they reach retirement age or until whatever restrictions you have on the plan occur. A lot of times, the plan is not real to them and they think they are just numbers on paper unless it’s explained to them regularly.”

He added that an ESOP can be a great recruiting tool, too, “if it’s sold correctly both internally to your employees and externally to the community and helping them to understand what it really is and what it means to our employees.”

At the same time, Skaggs says it’s equally important that this same level of communication be carried through to other stakeholders. “Customers and vendors all want reassurance that everything is going to be the same.”

While he, himself, was at first skeptical (“If everybody’s the boss, nobody’s the boss”), Skaggs says that he has since discovered that, besides greatly increasing the level of communication with everyone involved, not a lot else has to change when converting a company over to an ESOP.

“Your management doesn’t have to change or company governance doesn’t have to change. What the new owners expect is to know more about the business, they want their voices to be heard, they want to know when the employees as a group will have some kind of control over the business, they want some proof that they’re really going to benefit, and that it’s not just a bunch of numbers on paper they get sent to them once a year.

“They want a better understanding of how they can affect their ESOP account; what they can do to make their account grow into a bigger number for them,” Skaggs says.

He says Livingston Machinery management learned several things “the hard way” in getting its ESOP to where it is today. These include:

- You have to communicate … a lot

- You have to listen … a lot

- You have to educate … a lot

- You have to plan … a lot

- You have to involve your people in planning

Skaggs placed special emphasis on involving those who will become co-owners in the planning of the ESOP. “For them to feel like owners and to take ownership in what you want to do with the business, they must be involved to some extent of the planning.”

He also advised dealers considering an ESOP to plan for what Livingston Machinery calls “repurchase liability” for future buybacks of retiring or departing employees. “You need to plan your cashflow in such a way to be able to make those payments,” says Skaggs.

Share Meaningful Information

Agri-Service’s Schnoor, who has also served as president of the ESOP Assn., says, as much as anything, “Employees want to know that they have some control and proof that they are going to benefit from the effort they put in every single day. The great thing about ESOPs is the opportunity to tie that effort to real monetary benefit and the performance of your business.”

Schnoor went on to re-emphasize how successful ESOPs are characterized by continuous communication. “You need to talk daily about the things that employees can do personally to impact the business and how their efforts tie into the value of their shares. They need to hear this constantly.”

He suggests that, rather than talking about profits, management needs to talk in terms that people, especially those with limited financial acumen, can relate to. “It means more when you talk to them about how many boxes they’re throwing away every day and how the cost of each of those boxes and the tape that they’re using impact the company’s bottom line. You need to look for things you can put some pennies against.”

For example, says Schnoor, talk to them in terms of every dollar of sales and how much the dealership actually retains. If it’s 3%, 4% or 5%, explain that if it’s 3%, that means the dealership keeps 3 pennies of every dollar they take in. “I think breaking it down this way has more of an impact on employees.”

While much of the effort in establishing an ESOP is aimed at communicating with and educating employees on the concept, Schnoor says often times the bigger challenge is in management convincing itself that it has to look at its business differently.

“Some owners don’t like to talk about profits or about how much money they make because they feel like their employees don’t understand how it all works and what it means, says Schnoor. “There’s been a lot of studies that show how much more employee engagement ESOP businesses have compared to others, and how much better they do on a profit basis because they get their employees much more involved in the business.” Engaged employees are the result of sharing meaningful information they can relate to.

Not Democracies

Schnoor stressed the fact that ESOPs are not “democracies” where every employee votes on every single thing that the company does. Everyday management should essentially stay the same, but typically the participants will vote in the case of large mergers, acquisitions and sales. But even these may be left to the discretion of the board of directors, depending on how they’re handled (such as a stock vs. asset sale).

He also warns that there will always be skeptics inside of the company who will question nearly everything that’s done and the reasons why. The first questions they will ask are, “Why are they doing this?” and “What are the owners getting out of it?” says Schnoor. “Hopefully, you have very few of these folks in your organization, but you’re going to have them. They’ll never believe anything you tell them.”

“The real power of ESOPs is when you can get your employees acting like owners,” says Barnett. “If you can accomplish that, then your company’s going to be very successful.

“How do you know when your ESOP is working?” Barnett asked. Answering his own question he described an incident that involved Wayne Hunt, the founder of H&R Agri-Power. “Wayne likes to stop by the shop in the morning and go in and talk to the technicians. He wants to see what’s going on and what jobs are in the shop. One day he stopped by the shop and left his truck running while he made the rounds. When he went back out to his truck, it wasn’t running. He was afraid something was wrong with it or maybe he had run out of gas. When he looked up, one of the senior technicians was smiling at him. He says, ‘Boss, you’re burning my gas now.’ At that point, we knew the ESOP was making an impact.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment