A newly patented process for “taking the temperature of growing crops” from aircraft flying nearly a mile above the field is promising to bring quicker notifications of plant stress than the popular NDVI monitoring usually associated with GreenSeeker technology.

Doug Howe, president of AirScout, the Pennsylvania-based company marketing the proprietary aerial thermal imaging and Advanced Difference Vegetative Index, says the technology detects a plant’s increase in temperature, a first indicator of stress, to within 0.03 degrees centigrade.

“The first thing a plant does when under any kind of stress is to begin conserving its own moisture. The result is transpiration and cooling evaporation slows, which causes the plant’s temperature to rise,” explains Brian Sutton, the Indiana farmer (and pilot) who developed the technology about 10 years ago. “Stressed plants really jump out in thermal images, which gives growers and consultants advanced notice to potential problems in the field.”

AirScout’s technology provides a resolution of 30 centimeters from observation altitudes of 5,000 feet above ground level, or 15 centimeters from 2,500 feet, says Howe.

Howe and AirScout agronomist Maykol Hernandez say Sutton developed the system after observing one of his family’s soybean fields from the air that consistently showed yield drag over several seasons, despite no visual or NDVI clues as to growing condition differences.

“Eventually, after he began exploring thermal imagery and full spectrum digital photography of the field, he realized one spot in the field stood out when measured for crop temperature. That spot dropped 7 bushels per acre in yield from the rest of the field, and it corresponded exactly with where a fence was built for winter cattle operations. The compaction of that activity was affecting yields,” Howe explains.

Dealer Takeaways

- Increases in real-time precision crop sensing will demand knowledge of new ADVI and thermal imaging technology.

- Patented imaging technique means more data to process on in-cab monitors.

- Growers must devote more attention to smaller areas of their farms on a timely basis.

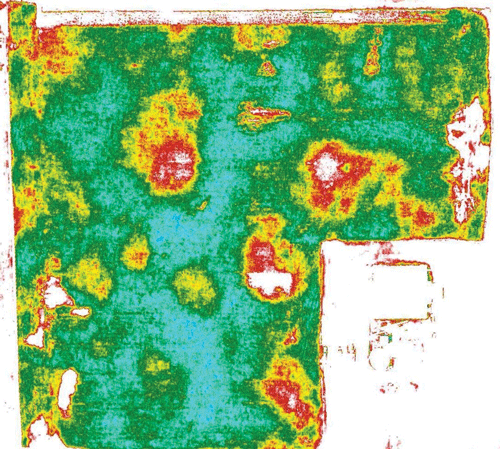

Unlike NDVI, which uses 3-4 segments of the light spectrum to measure “greenness” of a crop in its search for plant vitality differences, AirScout’s ADVI uses the full visible light spectrum, and Hernandez says this allows more precise differentiation of variability in the crop.

“Every pixel tells a story and with that resolution growers and consultants can be guided precisely to where problems may be occurring, long before those problems would show up as a change in leaf chlorophyll content,” he says. “With this kind of precision, we could conceivably lead a crop consultant to within feet of an affected plant in time to correct yield-affecting problems.

“Both our ADVI and traditional NDVI detect foliage color variations within a field that can tell you which plants may be lacking nutrients or moisture, but thermal imaging tells you when a plant is sick — like when you have a fever,” Hernandez explains.

This ADVI image employs both thermal imaging and full spectrum digital photography to provide nearly plant-by-plant monitoring with resolutions of 15-30 centimeters. Indiana farmer Brian Sutton, a principle in AirScout, developed the patented technology.

AirScout’s commercial system has been under development since initial tests began with it in 2012, Howe explains. “We started with a few test areas after the software and developing procedures were established,” he says. “Then, after the process was patented in May 2016, we began to ramp up in Indiana, Illinois and Michigan.

“We have field offices in Illinois and service providers throughout the country,” he explains.

Hernandez says AirScout’s tools allow the coverage of up to 320,000 acres a day with a single aircraft.

The company offers “one shot” overflights, along with 5-flight or 10-flight subscription plans which monitor members’ fields from pre-plant bare soil to harvest. In addition, the company offers prescription tools for variable-rate ground procedures and a “crop predictor” that Hernandez says allows a grower to predict ultimate yields in a field to within 2-3%.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment