Most seasoned salespeople will attest that the toughest and most time consuming sale occurs when having to educate customers about how products will benefit them. Teaching customers never deterred Michael Horsch of Horsch Manufacturing. By using a spade to turn over soil to show farmers and dealers how a new way of farming, along with his product, could improve soil, he built a $600 million global shortline company. By nature, he’s a farmer first and a manufacturer second; but his solution-driven design process, coupled with extensive travel and interaction with end-users, has enabled him to outsell much larger companies in niche markets.

Michael Horsch’s story starts in Germany, where his father, uncles and cousins got into farming in the early 1960s. Horsch says after the end of World War II, Germany was in the middle of the industrial revolution. “All the labor was going into industry and there were no cheap workers left for farming,” he says. “There were 200-500 acre farms run by Dukes and Lords and their labor ran away. So, they were looking for a way to either rent it out or sell. This was a chance for my father and his family to take over land in the ’60s and become crop farmers.”

Michael Horsch

Horsch says his family quickly realized that a two bottom plow and 35 horsepower tractor was not the tool for farming 1,200 acres. Plus, some of the land had just 5 inches of topsoil, with many rocks below. “As a 5 year old driving a tractor,” Horsch remembers, “I was pulling a trailer with guys walking behind, picking out rocks and throwing them in. There was a need to figure something else out to become more efficient, other than plowing the ground. Our family started looking into a min-till/no-till farming system, but there was no example for that. The scientists, local agriculture institutes and neighbors all said it would never work!”

During that time, the family’s farm was considered large, but Horsch was facing another issue; the land would not be enough to support everyone. “I had four younger brothers that also wanted the home farm,” Horsch says. “So, it was clear that not all five of us would be able to take it over from my father.”

Finding a Passion for Machinery

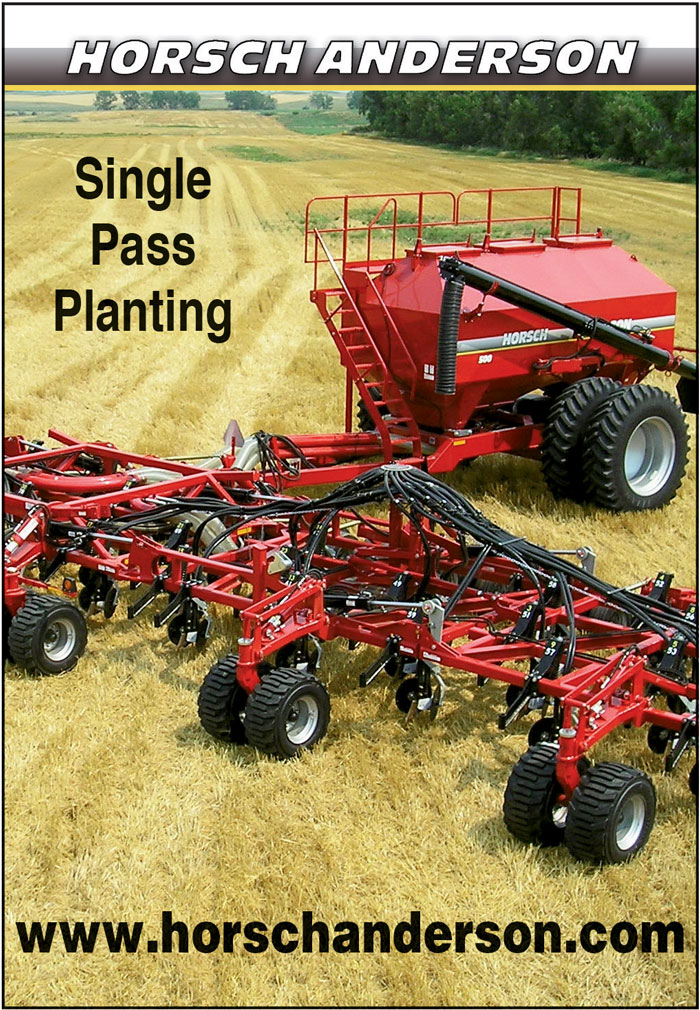

Horsch Manufacturing’s first advertisement in Farm Equipment appeared in the October/November 2007 issue. The company was branded as Horsch-Anderson in its early days in North America. Horsch came into the North American market through Kevin and Kory Anderson.

As a Mennonite, Horsch took advantage of a church-sponsored program to travel to the U.S. and work on farms. His father had been a part of a similar program in the late ’50s. “He always talked about this and showed me pictures from Nebraska and Iowa where he was a trainee. In the ’70s, that was the only way to stay here for at least a year and have a working permit, otherwise you could only come for 3 months. So, I used this with the idea of finding a piece of land and becoming a farmer in North America. That was the dream of an 18 year old.”

“I had to go back in late ’79 because my visa ran out,” Horsch says. “It had to be resubmitted from Germany and my intention was to immigrate here. The problem was the German government didn’t let me go, because I hadn’t done my service. In those days, you had to do army or civil service and without it, you couldn’t get another permit to leave the country. That was the start of the company, I had to do my civil service and then during evenings I was drawing up machinery and building no-till seeders.

“Problem was, there was no machinery available,” Horsch says, “so we had special machinery built. Then, we’d start cutting it up and rebuilding it. My father, who was rough on machinery, was always getting his ax and cutting stuff up, attaching railroad ties to it and changing openers. I always hated that he’d cut up the nice machinery with paint on it and didn’t put paint back on. So, I had ideas that when I built my own machinery, I would make it nice and work the first time.

“I made simple drawings and then went out in the workshop and started putting steel together,” Horsch says. “I had to find a way to lift up the straw, place a seed underneath, and then put the straw back on top. When my father and uncles found out I was onto something they said, ‘Get it done. Here’s some money if you need it. Build me one also.’ This is the spirit in our family; if somebody has a good idea, nobody says that you shouldn’t do it. Sundays after church, we walked fields with a spade, dug holes and learned how soil changes. Earthworm population went up and water infiltration went up with less tillage. We dealt with issues with weeds and so on and that was the start of the Horsch Machine Company.

“In 1980, I had the concept going and, in ’81, I built the first Seed Exactor for my father,” Horsch recalls. “The machine was the first rotary base with a seeding bar underneath; it was a no-till or maximum no-till seeder. Disturbance in those days wasn’t quite the way we wanted to place seed. Obviously, we’re not in a corn and bean country where I grew up, it’s mainly winter wheat. So, instead of putting seed down in rows, we wanted to scatter it. It was a solid seeding system with no rows, but with no contact with trash because we had problems when we had too much residue in contact with the seed, it was rotting.”

Horsch, at the age of 21, had the opportunity to refine the machine due to family demand. “Every three or four weeks I had to build one for an uncle, and then another uncle, because the whole family wanted one. They told me if it didn’t work, they’d help me make it work. As I kept building machines, I realized that it was a way to make money and to get into farming in a bigger way. Then obviously, I got stuck with debts and commitments, and the dream of becoming a farmer drifted away. In 1984, we officially started Horsch Machine Company.”

‘Educational Marketing’

Horsch was ready to take on the world. “I thought I could sell all farmers my no-till seeder, teach them how to use it and make them stop plowing. It didn’t take long to figure out I had something nobody wanted. I couldn’t tell farmers, ‘This is what I have and you better stop plowing.’ The guy would say, ‘You’re 23 years old, have no degree, and telling me what farming should be like? Get outta here.’ They wouldn’t believe me.”

Listen to the story of Horsch Manufacturing in founder Michael Horsch’s own words on the “How We Did It: Conversations with Ag Equipment’s Entrepreneurs” podcast.

That’s when Horsch hit on an idea to show the concept using the shovel, or spade. “I had to go far from home and find larger farms that had heavy soils or lots of rocks and a problem with plowing and efficiencies. Then invite them to come to our farm, take the spade out, dig holes and explain, ‘Look what happens after 15 years when you don’t plow.’ The structure changes, the earthworm population goes up, soil gets more active, water infiltration goes up and the yields are not any worse than plowing.

“We started with a spade, selling the idea, but not machinery. It took ages — they came back and looked at it again in springtime and summertime. Eventually, they wanted to implement it on their farm and then needed equipment. Instead of selling equipment, we sold them a different method of farming. I call this ‘Educational Marketing.’”

Horsch says his break came when East and West Germany were reunited in 1990. “My home farm was half an hour from the iron curtain. Before, we never went there because it was really a wall. Then, overnight, we had access to large cooperative farms between 3,000 and 10,000 acres in our backyard. Those farms had never ever had any western equipment; it was all Eastern European and Russian — you can’t imagine what junk it was. Those farmers were desperate and wanted only machinery from the west.

“Nobody was ready for the wall coming down. I had maybe 20 people employed and was breaking even, with revenue of probably $2 million in 1990.” Horsch continues, “Those cooperative farms were pushed into private hands because the communist governments pulled out. The farmers didn’t necessarily own the land, but they had a right to farm it, and had good people willing to work for little money to continue. If you had a crop, you could sell it for real money instead of rubles or East German deutschmarks, which weren’t worth anything. If you could survive for a year or two and have a good crop, you could start buying equipment.

“After the wall came down, I was traveling to East Germany,” Horsch says, “knocking on doors of cooperatives and building relationships. Those people were interested in talking because they never before had access to West German equipment or what was available since they couldn’t travel. Information wasn’t flowing at the time. I sold quite a bit of equipment just on handshake deals, because the only means of payment was the East German deutchmark and there was no plan for business to be legalized.

“The exchange rate was 3 East German deutschmarks to 1 West German deutschmark,” Horsch recalls. “In those days, we were making three-wheeled self-pulled seeders that cost 300,000 deutschmark, so it was almost 1 million East German marks. We signed orders that said, on delivery, we’d get 900,000 East German deutschmarks. But 6 months later, the exchange rate became 1 to 2. I had a couple deals done where I was making quite a bit of money.

The foil maize seed drill was Michael Horsch’s first development of his own, which at that time was designed within the agricultural purchasing and sales company Horsch OHG Landau / Isar. He officially started Horsch Machine Co. in 1984. Photo courtesy of Horsch

“In those days I needed the money, says Horsch. “But my Uncle Walter, who was my mentor and helping me run the business said, ‘We have to give the money back; it’s not right.’ So, I sent the difference back to the farmers. Those people, if still alive, remember it today. Even the next generation of farmers remembers that their father, who passed on the business said, ‘We will remember you, one of the few West German businessmen that did not pull us over the table.’ This is our attitude, not only with East German farmers, but with all customers.”

“Instead of selling equipment, we sold them a different method of farming. I call this Educational Marketing…”

As Horsch’s company experienced explosive growth in former Communist areas, he finally realized his dream. “Obviously not all the cooperative farms survived, and this is how we finally got into farming. Today we farm about 55,000 acres. This is why we’re different than any other shortline seeding and tillage manufacturing company,” Horsch says. “We’re education marketing driven. All we did in the last 35 years is increase the scale of selling with a spade. We have farms in the Czech Republic, Germany and France and we bought a small farm in North America and we have partnership farms in Ukraine and Russia. Now we’re working one in Brazil.

“All those farms are cropping systems centers,” Horsch says, “and trying to develop new regional ideas. I cannot take what I do on a German farm to France, because of different rotations and climates. You have to look at each market when you introduce new tillage methods, the rotations that are common and how to improve with different fertilizer placements or incorporating straw and so on. We’re not competing with scientific research, universities or other research organizations, but in a way we’re trying to bring things together and make it practical.

Exclusively Online

Read more from Farm Equipment’s candid interview with Michael Horsch and other coverage.

- [Podcast] Conversations with Ag Equipment’s Entrepreneurs: Horsch CEO Michael Horsch

- Horsch Farm Equipment’s Owner & Founder Michael Horsch

- [Video] Horsch & The Customer-Manufacturer-Dealer Triangle

- [Video] Prescription Farming vs. Management on Horsch’s Own 8,000 Farm

- Boots & Spades Needed, Not Gigabytes

“We offer seeding, planting, minimum tillage and spraying — those are our four core business specialties. Most competitors in Western Europe build for small-scale farmers. We come from a larger-scale minimum till and no-till farming background. In those four areas we are technology-driven, we have 120 engineers and the R&D is controlled by my brother and me. Most products we develop for our own farming. We have a need for something due to a certain soil issue, we want to grow a different crop, or we don’t like the tillage we’ve done so far, so we’ll build a product for it.

“When we needed a new planter,” Horsch says, “we would build one for ourselves and the design would be unique. We didn’t look for whether there was a market for it and never had an intention to build large planters, with 40-foot to 60-foot bars. But now we’re No. 1 in Eastern Europe, which the dark green guys obviously don’t like.”

Expanding into North America

Horsch says he’s been doing a lot of travelling to North America recently to bolster the company’s presence here. “I know the Midwest like the inside of my pocket, as we say. I like the countryside, the crops, the farmers, the mentality, and for over 40 years I’ve built lots of friendships there.”

There was only one product available when Horsch broke into the North American market in early 2000, a 60-foot air seeder with a 500-bushel seed cart. He says it was only sold in the Dakotas. “Butler Machinery was our sole dealer. Eventually, we went into Canada and south. We were the first ones bringing in the compact disc in the vertical tillage business. I think, by numbers, we have sold the most compact discs in North America. Then we started growing into other areas with more dealers and offered planters, and that helped us grow, especially into the corn belt.

“A lot of products available for Western and Eastern European markets, both in seeding and tillage, also fit the U.S. market,” Horsch says. “We have a factory and engineering in North Dakota, so everything we sell here doesn’t 100% come from Europe. Some of the basic designs come from Germany, but it’s built here with 80% local content and adapted for the markets here.”

Michael Horsch first started participating in farm equipment shows in 1982 in Munich, where he officially kicked off sales activities. Photo courtesy of Horsch

Horsch says some of his peers are trying to bring European equipment to the U.S., but his knowledge of the market makes him skeptical of the potential. “If it’s not Americanized, it will not be successful,” he maintains. “Your ‘taste’ is different. The guys in Russia and the Ukraine have scenarios like in the corn belt with big farms, wide rows and open roads. They could easily buy North American equipment, but they don’t, because their taste comes from the Western European side. That equipment also has a taste.

“Look at the cars,” Horsch continues, “a BMW or Mercedes that’s built in North America looks different than in Europe, because you have different tastes. In farm machinery, it’s very important that things have to look right. We have some products we successfully bring over from Germany and Europe, because they are built to American taste. But there’s certain other equipment which I would not want to bring here because it isn’t right.”

Regardless of the market he’s in, Horsch has witnessed phenomenal growth. “From 2000 until today, we grew by 25 fold,” he says. In seeding, large planters and medium tillage, we only have Deere in front of us by revenue. Everybody else, we’ve passed in these segments.”

While Horsch wants a bigger footprint in North America, he says it takes a serious commitment to sell his products. “In a way I’m not a good salesman for dealers. I can scare them off as well as I can attract them, because I say, ‘Guys, be very careful working with us. It’s a long, rough journey. It could be an expensive journey, not always a win-win.’ If they don’t understand what we’re trying to do, it’s not going to take us very far.” If a dealer doesn’t own a spade and have the desire to get out on farms, he might not fit the culture.

With 2,000 employees, many different products and 6 factories all over the globe, Horsch says the philosophy hasn’t changed. “It’s important that we continue to do what we did when I started 37 years ago, we have to be as close as possible to the customer. That’s what counts, nothing else.”

To read more from Farm Equipment's Ag Entrepreneur series, click here.

Farm Equipment‘s Ag Equipment Entrepreneurs series is brought to you by Ingersoll Tillage.

Ingersoll specializes in seedbed solutions. Whatever seedbed challenges you have, Ingersoll can give you the right tools to get the job done. For every tillage and planting practice, there's an ideal Ingersoll application, visit www.ingersolltillage.com.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment